Slippery Fish. Unpacking “Good Urban Governance” to Mobilise Investment for the NDCs

Good governance is key for achieving the national CO2 emission reductions, known as Nationally Determined Contributions. But the “how-to” remains undescribed. Scott A. Muller presents us with local experiences to close this gap.

“Countries will need to reconfigure their governance systems.” This was one of the key messages that emerged from the critical mass of government officials and international participants in the First Global NDC Conference in Berlin (2017) regarding the question of how climate actions can result in tangible development benefits.

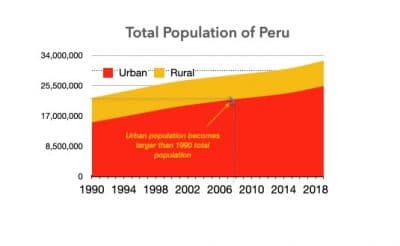

Unfortunately, despite universal calls for “good urban governance,” our transformational knowledge on “how” to achieve that is specious. The majority of nations’ CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement production are rising faster than their rate of urban population growth, which again is increasing faster than their rate of national population growth. The NDCs from many developing countries do not yet represent a vision of the country that integrates national and local policies and planning. The challenges presented by continued urbanisation, social inequities, and rising CO2 emissions emphasise the need for innovative governance strategies.

Population dynamics and urbanisation in Peru over the last three decades © Scott A. Muller, 2021

As a fundamental step towards improving our understanding of how to reconfigure governance, seven different partner countries supported by the International Climate Initiative (IKI) established a learning theme on integrated governance within the multinational programme “Mobilizing Investments for the Implementation of the NDCs” (IKI MI). Between April 2019 and June 2020, three distinctive evolving governance scenarios were explored under Learning Theme 3: valorising solid waste at the municipal level (Peru), aligning county integrated development plans with the National Climate Change Action Plan (Kenya), and implementation of the Energy and Conservation Act by Local Government Units (the Philippines).

This has produced a wealth of “how-to” transformational governance insights from experiences shared by local leaders.

“Good Governance”

To be clear, over past decades the concept of “good governance” has recurrently been presented as the missing link to successful growth, sustainable development, and economic reform. So, with “good” as the goal of innovation, it must be recognised at the onset, that we are talking about a slippery fish.

Firstly, the term is amorphous and has very diverse understandings across cultures and generations. In the 1990s, “governance” became fashionable as a “management term”— gaining popularity across diverse sectors, with different meanings. In both the private and public sectors, “governance” became quite a general term across managerial, political, and economic discussions.

With the “Millennium Declaration” issued by the UN Generally Assembly in 2000, “good governance” was identified as a specific, fundamental precondition in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Kofi Annan called good governance, “the single most important factor in eradicating poverty and promoting development.” While a step in the right direction, “governance” itself was not adopted as a stand-alone MDG. With the nebulous use of the term, there was simply no clear indicator or way to measure “good governance.” Interestingly, despite lacking a clear definition, the mid-programme progress report identified “governance failures” as one of the overarching reasons for the shortfall in the attainment of the MDG targets.

The historic meeting room in the old city of Arequipa (UNESCO World Heritage Site) is decorated with paintings of a hundred famous Peruvians, all of them men. The majority of local environmental authorities and solid waste managers who participated in the technical consultations in Peru were women © Scott A. Muller, 2021

And over time, these general governance failures (i.e. what “good governance” did NOT look like) helped a common view to emerge, on what the particular technical attributes of “good governance” were and what is their specific role in improving human development. In fact, by 2015 the practical experiences and studies on “good governance” in the MDG programmes allowed a specific Governance SDG to be created: Goal 16 to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.”

While good governance is indeed a pillar throughout the SDGs, (e.g. Goal 11 Sustainable Cities, “cities and public governance”), Goal 16 remains the most elusive of the 17 SDGs—with the highest number of targets (12) and the lowest means of implementation.

It remains a persistent challenge to collect data and innovate strategies to overcome political and cultural gaps and barriers. Nevertheless, it is progress that in the multilateral space, we are aligning the attributes of “Good Governance.” And thanks to forward-thinking programmes such as the IKI MI we are progressing on how to actually innovate governance in that direction.

Integrating Governance to Mobilise Investments

Effective investment, across all sectors, requires coordination between national and subnational governments. More specifically, the capacity to lower emissions and adapt to climate change depends on the relationship between the different levels of authority in the country, with special relevance to urban environments. And hence, integrating governance becomes the skilful shepherding of slippery fish.

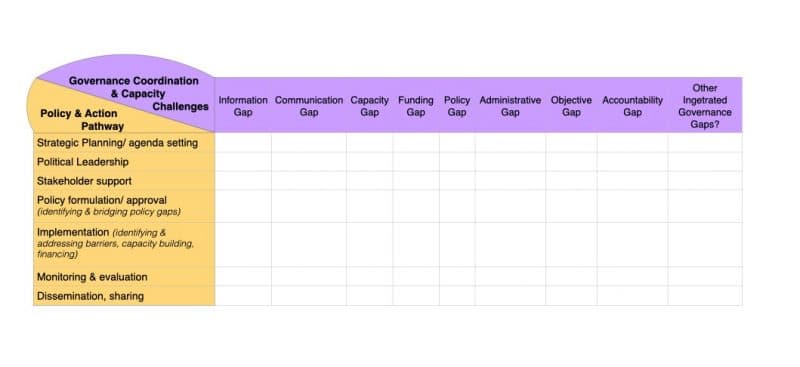

The Multi-level Governance Diagnostic Tool used by national and local authorities © Scott A. Muller, 2021

To be sure, the activities under Learning Theme 3 facilitated intensive sharing and debate on governance experiences and challenges for more effective NDC investments at the local level in Peru, Kenya, and the Philippines. Across the 3 countries, a tremendous amount of information on the challenges related to governance that stunt the competence of NDC investments was generated—not only on particular domestic matters, but common threads emerged as well.

To give away the ending: no amount of financial investment is going to transform our cities. Mobilising investment becomes more about establishing favourable conditions for financing, as opposed to simply increasing availability or access to financial resources. This requires transforming governance. The sooner, the better.

- Slippery Fish. Unpacking “Good Urban Governance” to Mobilise Investment for the NDCs - 24. September 2021