Resilience After Covid19 – A System-Thinking Approach

Resilience needs to be a priority in shaping the post-pandemic future, argues David Jácome-Pólit, outlining the advantages of system-thinking in urban planning.

The world has been severely affected by the Covid19 crisis. A rising number of infected people and related fatalities have shown us that the human relationship with nature needs to be revised and that we need to rethink how different human systems work. Thinking in systems is a promising approach to such highly complex issues like the pandemic: instead of focussing on fragmented solutions, it allows urban planners to look at equally sophisticated responses and come up with long-term solutions.

In this light, two key concepts should guide our planning for the post-pandemic future as well as for future environmental crises and other natural or manmade challenges.

Functioning Systems Go A Long Way

First: Any system has a better chance to face and emerge stronger after a disturbing event if the system has worked properly before the event happened. Around the world, different examples of how the Covid19 crisis has been handled are proof to this.

Medellín, Colombia, could rely heavily on a culture of fostering social, environmental, and technological innovation, and in turn on an already-in-place human, physical, and financial infrastructure when the virus arrived in Colombia. This allowed the development and use of technologies to support contact tracing, to slow down contamination and infections, better communication with the population to distribute guidelines and instructions, and fast provision of respiratory support by producing low-cost machines.

In Mongolia, thanks to the National Management of Emergency Agency’s COVID-19 task force and its efforts, the government was enabled to take systemic actions to prevent possible infections coming from foreign countries. By coordinating actions, by integrating different agencies, and by using information technologies, the country suspended important cultural celebrations and managed to shut down possible hot spots before they occurred. As a result, the number of infections was kept at low levels and even allowed to country to help out its neighbours’ struggling food systems, for example providing support to China by donating 30,000 sheep.

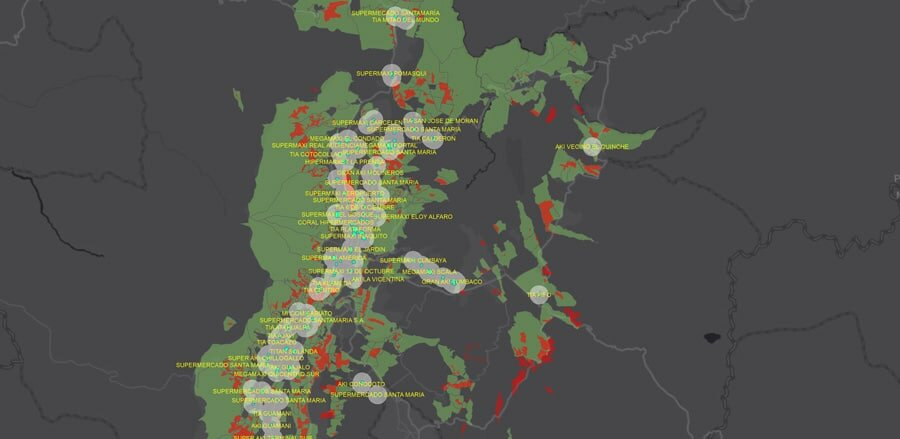

In Quito, Ecuador, a solid understanding of how the local agrifood system works has allowed the city to cope with the challenge of distributing food to those who were hit hardest by the pandemic and its implications. Being able to build on previous efforts to strengthen the food system, the city had already identified malfunctioning links along the food chain, such as “food deserts” in certain parts of the city, where food distribution and sales are very limited.

Availability and concentration of vulnerable population © Municipality of Quito

Furthermore, the city had already identified vulnerable population by groups: age, gender, poverty, or (dis)abilities. This allowed providing effective, localised, and tailored help. Additionally, the city had also collected valuable knowledge on successful urban farming as a means for city dwellers to produce local, organic, and healthy food for themselves and for others.

Building Resilient Systems

Second, we need to think of resilience as a potential property of a complex system. This system can be a mobility system, a water distribution system, a production system, or a social system.

One important strategy to build resilience within a system is to create redundancies (for example redundancy in health infrastructure or food distribution infrastructure). However, this may be difficult to achieve in contexts with a lack of data on the population and with high levels of informality in different types of markets, or with insufficient economic means to provide physical infrastructure.

In these contexts, other strategies can contribute in different ways to resilience building and should therefore be taken into account. Among them, distributed governance, diverse and participatory planning processes, and the strengthening of a city’s social capital have proven to be an advantage, as examples from cities around the world underline.

In Nairobi, the Dandora Transformation League (DTL) is stepping up efforts to contain Covid19. A pilot project in hope of scaling up, DTL members ensure that surfaces are being disinfected and that sanitation stations are being set up at the entrance of public buildings and inform people on the importance of hand-washing and other hygiene measures. The DTL is a non-profit community-based organisation, located in the suburb of Dandora, which used to be characterised by high crime rates, youth gangs, theft, and the accompanying negative narrative. DTL started as a grass-root movement, with a self-governance structure that succeeded in changing this for the better through a collaborative and participative effort, making meaningful changes to this part of Nairobi.

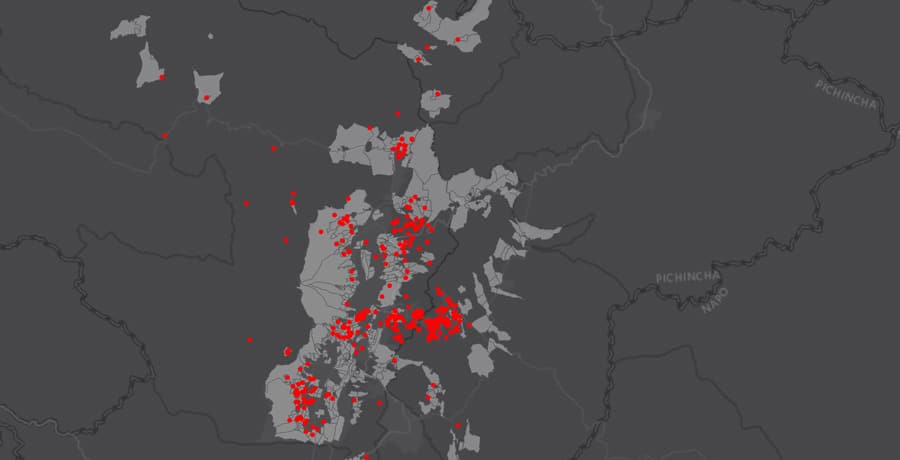

In the city of Quito, community self-organisation and especially the support of neighbourhood leaders have proven to be effective amplifiers of public efforts in fighting the spread of the virus. Elected through the participatory system of the city, neighbourhood leaders, the majority of whom are women, have become important partners to public officials. Those leaders, who naturally know the territory and its inhabitants better than most officials, have helped to identify those in need of help, such as non-Spanish speakers, or people who are not able to leave home due to health impediments. They have helped to quantify more accurately the aid needed, thus contributing important efforts both to organising the assistance provided and to communicating guidelines and instructions from authorities within the neighbourhoods.

Concentration of vulnerable population (grey) and vulnerable cases with special needs identified by neighbourhood leaders (red dots) © Municipality of Quito

The city of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, has taken important measures to respond to the Covid19 crisis, such as supplying sanitisers and food at affordable prices, and distributing water to minimise water shortages. In this setting, the social capital in the response capacity is strengthened with the addition of 30,000 youth volunteers to the already committed police and security forces.

It’s All About Design

The most important thing about solutions is how you design them. Plans, strategies, and projects should always address cities’ two fundamental challenges. First, the need to provide better livelihoods and quality of life to their citizens, which in turn requires a balance between economic prosperity and social inclusion. This has to happen without crossing those environmental boundaries within which we expect that humanity can operate safely, that is to ensure sustainable development. Second, the need to prepare for and to cope with events that threaten the safety of people and / or the continuity of the city’s various functions and services, that is to ensure resilience capacity.

A system-thinking approach, looking at how different systems operate and influence each other, promises to include these two aspects and thus make cities more resilient to current crises like the Covid19 pandemic and beyond.

- Resilience After Covid19 – A System-Thinking Approach - 18. June 2020

- Empowering Communities to Build Resilience: Quito, Ecuador - 1. October 2019