Positioning Medellín for a more Sustainable Future

Many transitional cities have worked hard to develop planning tools that make a difference in people’s lives. And while Colombia’s “City of Eternal Spring”, Medellín, has made significant progress, it should now take it to the next level to become fully compatible with global sustainability agendas. By Santiago Mejía-Dugand

Colombia and Medellín have had a complicated history, and they are going through difficult times as I write this article. For Medellín, it has been a roller coaster: in 1947, Life Magazine hailed it as a “sort of capitalist paradise [where] nearly everybody makes good money and lives well”. In 1949, the Readers’ Digest forecasted that a second conquest of South America would come from Medellín, the “cleanest from Canada to Chile” and, according to a local industrialist at least, social gaps did not exist.

In the following decades, massive, forced displacement of rural inhabitants fuelled its rapid growth. After being the “cleanest in the Americas,” many of its inhabitants were now living on a garbage heap – literally. The municipal dump rapidly became a 60-metr mountain and residents, especially those living from recycling materials discarded by the city, started building their shacks on top of it. Supposedly inexistent social gaps became more than evident, and violence reached its highest levels.

The 2000s came with good news for the city. A new political elite recognized the historical debt with the urban poor and developed important infrastructural, cultural, educational and social projects, following a management and urban planning strategy later called ‘Social Urbanism’. High architectural and engineering quality were inevitable components, and a strong focus on citizen participation grew to become an important part of the city’s governance.

Most innovations required reimagining city life and signing new social contracts: new urban education and culture, and transformations strategically located in places with inequity and violence problems. Some of these infrastructure projects were even found to have a direct impact on crime statistics. These interventions demanded the development of new protocols, new methods of institutional articulation, and new tools and arenas for participation.

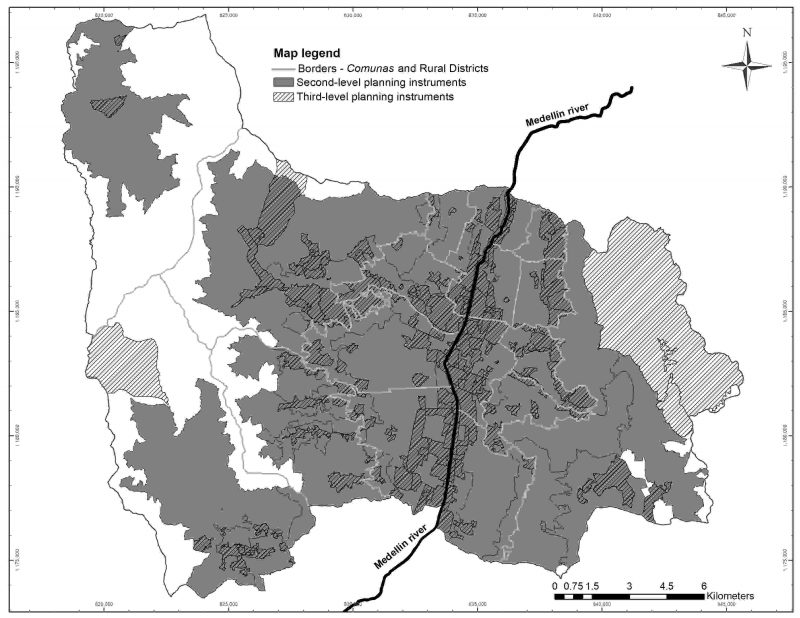

Second and third-level planning instruments designed to change socio-spatial realities in Medellín © Mejía-Dugand and Pizano-Castillo, 2020

Aligning global sustainability agendas and local planning instruments

Indeed, many low- and middle-income cities, such as Medellín, have fought hard to improve the lives of their citizens. Much of these efforts have undoubtedly impacted the city’s liveability and environmental performance. However, before the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and now the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – especially SDG goal #11 “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” – there were no clear frameworks that would facilitate feedback, monitoring and accountability. Sustainability is not explicitly part of many of these cities’ agendas.

The Center for Urban and Environmental Studies (URBAM) at EAFIT University, is doing research to find ways to connect global sustainability agendas to existing mechanisms that are designed to impact socio-spatial realities in the city (see Figure 1 on the areas covered by current planning instruments). Funded by UKRI’s Global Challenge Research Fund, URBAM has analysed these planning instruments in order to make SDG localisation easier.

The city is one of few in the region to have advanced with its SDG localisation efforts. With the issuing of Agenda Medellín 2030, it went through great efforts to translate SDGs into local priorities, connect them with ongoing projects and establish targets. What we found is that while this is a great step, it is not enough to fully localise SDGs. The implementation strategy must be connected to the tools the city uses to pursue its vision of how the future Medellín should be.

We reviewed all city documents relevant for the implementation of SDGs, such as the Master Zoning Plan, the Development Plan, Borough Development Plans, and technical support documents. Few mention SDGs and only one includes them in a systematic way.

Second- and Third-level Planning Instruments can Lead the Way

The Master Zoning Plan (Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial – POT –, in Spanish) is the only first-level planning instrument. It defines, in a general way, the city’s occupancy model (i.e., how the city will grow and develop). However, it does not pursue this vision by itself – complementary planning, financing and management instruments are needed to do so. Such second-and third-level planning instruments have a narrower geographic and normative scope, which can land this general vision and comprehensively transform low-scale administrative divisions, such as boroughs and neighbourhoods.

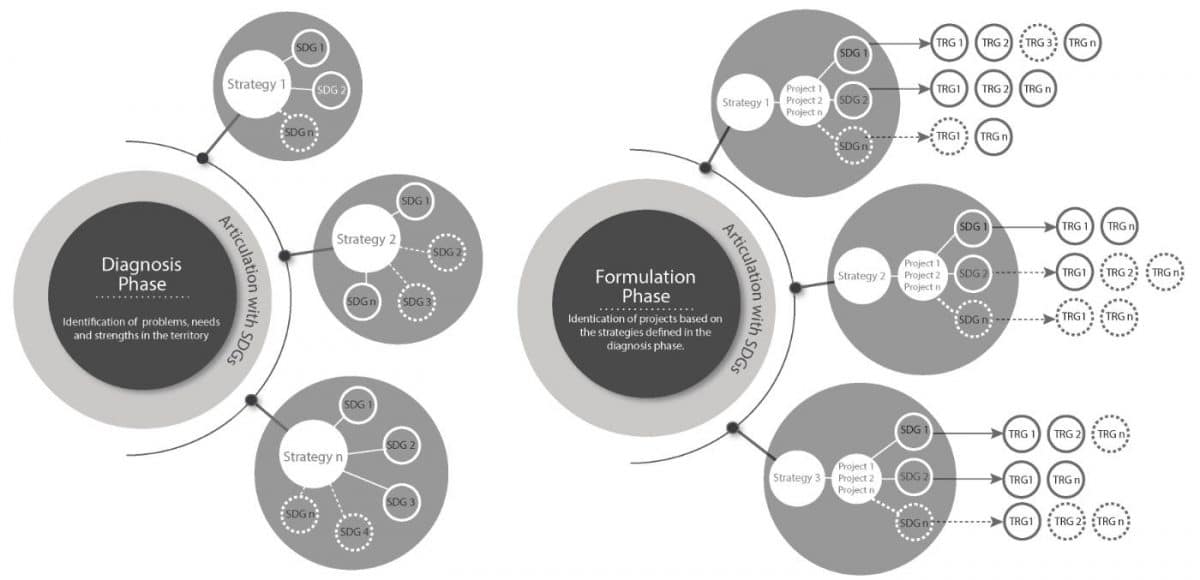

Important second and third-level planning instruments in Medellín currently do not include SDG analyses. This is a lost opportunity, considering that the lives of Medellineans are impacted by their government through these instruments. We have thus suggested a simple framework for the inclusion of SDGs already during the diagnosis and formulation phases of urban planning instruments (see Figure 2).

Before planning instruments become norms, they must go through two different phases: diagnosis and formulation. In the diagnosis phase, needs, problems and strengths of different types are identified (for instance, related to housing, public space or utilities), and strategies are defined to address them. The formulation phase defines specific projects based on those strategies, which then lead to the issuing of an administrative act (i.e., a decree, an agreement or a resolution).

It is very important to include SDG considerations already in these early phases. This would allow for better monitoring and, more importantly, a better understanding of the connection between actions and outcomes. Figure 2 illustrates our suggestion about how this connection can be made.

Figure 2: Framework for inclusion of SDG targets into diagnosis and formulation phases © Mejía-Dugand and Pizano-Castillo, 2020

Sustainability requires political will. Many of the decisions that need to be taken are political in nature. However, robust science-policy interfaces are also required. Planning instruments offer a technical, evidence-based contribution that has been proven to work in cities around the world, particularly in transitional cities such as Medellín. However, they must be connected to concrete SDG targets already in their early diagnosis and planning phases.

Many cities have shown interest in what some have called the “Medellín Model”, and many have adopted or adapted Medellín’s planning instruments and governance models. We know they are compatible with the SDG framework. Why not take advantage and build on what is already in place to further advance the local implementation of the SDGs?

- Positioning Medellín for a more Sustainable Future - 13. July 2021