Urban Governance for Sustainable Global Development: From the SDGs to the New Urban Agenda

By Eva Dick

The urban community has widely celebrated the adoption of SDG 11 – “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” – as “stand-alone urban goal”. The step is perceived as reflecting an increased awareness of the important role of cities for global development pathways.

Although sharing this positive assessment, this paper argues that for an effective follow-up to Agenda 2030, issues of urban and local governance ought to be addressed in further detail and as cross-cutting issues. The paper identifies urban governance issues that are presently neglected in the SDGs and require further elaboration.

SDGs and urban governance

The urban dimension of the SDGs goes far beyond Goal 11. In order to effectively follow up on the majority of the SDGs, the urban (governance) dimension and/or interlinkages with the “urban goal” must be specified. This argument is informed by the following three assumptions:

- Much more than just places, cities are increasingly becoming drivers of global sustainable development.

- Implementation of most SDGs requires local-level action.

- Current conditions and frameworks of urban governance do not allow cities to adequately fulfil the functions spelt out by the SDGs (Cobbett, 2015, p. 1).

But to what extent is urban governance precisely accounted for in the SDGs? In what follows, the focus is on the “urban” goal (SDG 11), the “governance” goal (SDG 16), and two sectoral goals, SDGs 13 (climate) and 9 (infrastructure).

The urban goal (SDG 11)

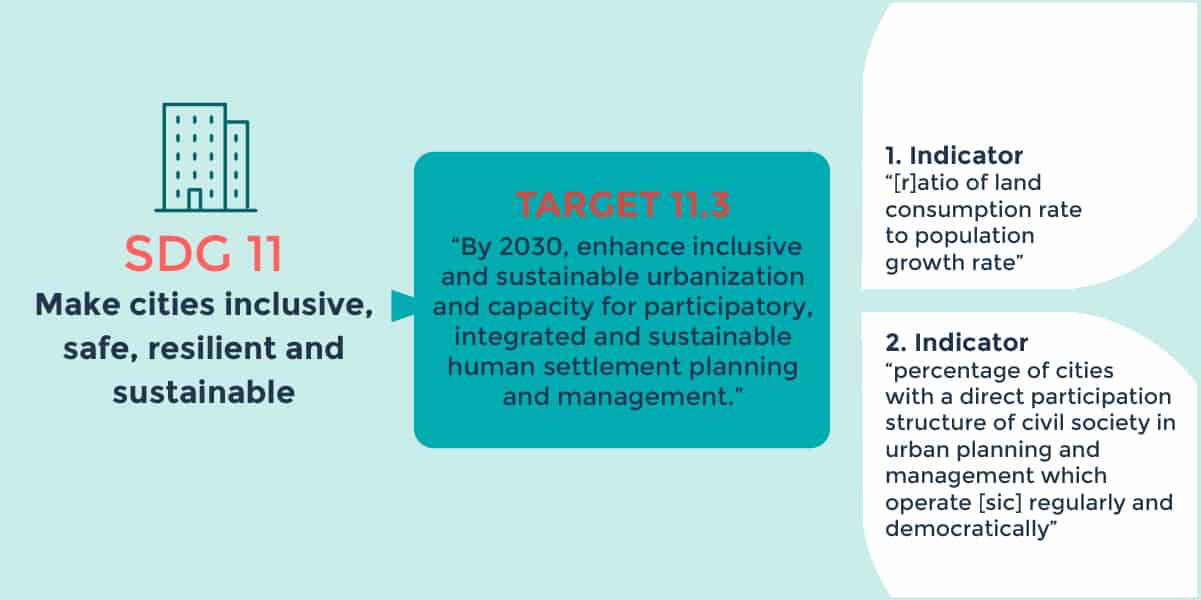

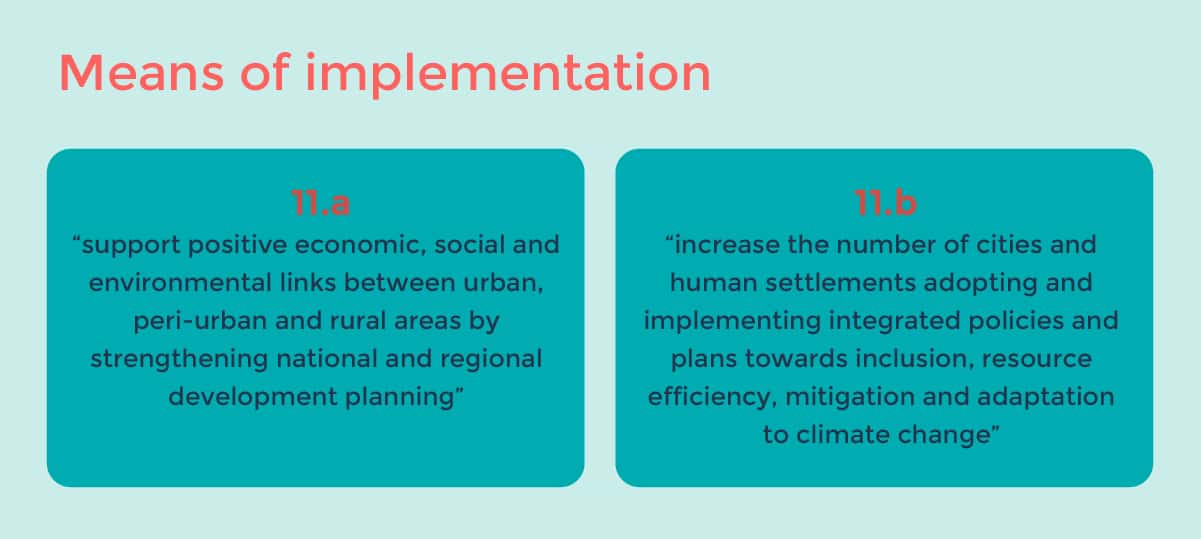

Although SDG 11 includes references to urban governance, no distinct (good) governance target was defined. Important governance aspects are, however, mentioned in target 11.3, as well as the means of implementation targets, 11.a and 11.b, including some mutual overlaps. While important aspects of urban governance are covered, framework conditions (e.g. municipal finance, inter-sectoral planning frameworks, capacity-building) and tools for achieving integrated planning and management are not addressed.

Multi-level and territorial governance issues are taken up in 11.a; however, the important role of national urban policy frameworks is not elaborated on any further. In 11.b, both presently retained indicators make reference to local and urban disaster risk-reduction strategies and implementation in line with the Sendai Framework Indicators. It is recommended that the role of vulnerable and marginalised groups, for example informal settlers, be specifically taken into consideration in risk-reduction and resilience strategies and mechanisms.

The governance goal (SDG 16)

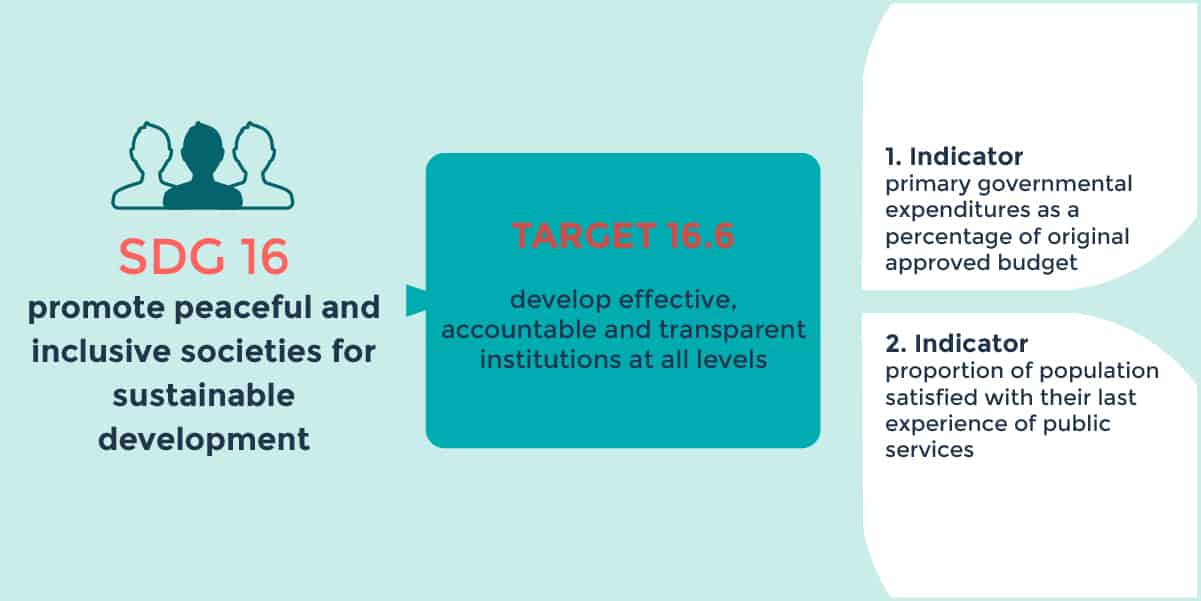

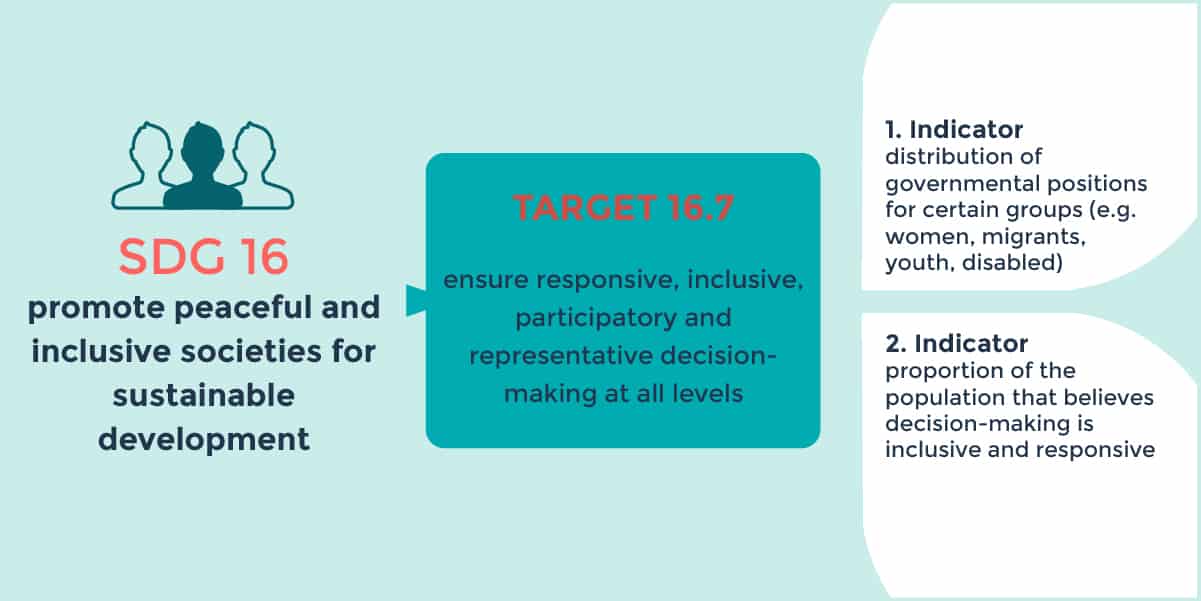

Both in goal 16 and in its ascribed targets 16.6 and 16.7, there is an implicit – but no explicit – reference to local and urban governance.

The goal’s indicators are certainly relevant for all governmental and administrative levels. However, the distinct leverage of the urban context with regard to good governance (e.g. spatial proximity of diverse and active constituencies) and key frameworks (decentralisation, subsidiarity, administrative capacities) and mechanisms (e.g. residence-based rights, participatory budgeting, public-private partnerships) to bring this potential to bear should also be mentioned. Moreover, frameworks determining interrelations between different scales of government should be referred to. These are a pre-condition for local or urban governments to effectively exercise their rights and duties vis-à-vis their constituencies.

Imbalances in access to political power and opportunities to participate in public life are particularly pronounced in cities, alongside social and economic inequalities. Thus, tools and instruments to enhance participatory processes, particularly considering urban fragmentation and informality, must be elaborated. Furthermore, there are obvious interlinkages with targets 11.3 and 11.b, which should also be further elaborated.

Other (sectoral) SDGs

Many other SDGs and targets also have a clear relationship with local- or urban-level action but lack the corresponding references. According to Misselwitz and Salcedo Villanueva, “21% of the 169 targets can only be implemented with local stakeholders, 24% should be implemented with local actors and a further 20% should have a much clearer orientation towards local urban actors” (Misselwitz & Salcedo Villanueva, 2015, p. 18, emphasis in original). SDG 13 on climate change is a case in point, as it does not explicitly refer to the urban context and to governance challenges for effective and socially just climate adaptation. Another example is Goal 9 on resilient infrastructure, in which no reference can be found on the role of urban actors in identifying, providing and financing adequate infrastructure. This goal and the ones on health, education, water and sanitation as well as energy provision strongly interlink with Goals 11 and 16. In view of the urgency of (new) urban infrastructure investments and the resulting leverage of the sector for breaking up unsustainable path dependencies in global development, the urban reference must be made clearer.

Complementing the indicators will not close the implementation gap per se but provide guidance on future developmental priorities and required data collection for monitoring progress. However, before this potential is brought to bear, considerable technical constraints with regard to the effective measurement and monitoring of the indicators must be resolved. Among these are the lack of spatially disaggregated data, problems of “SMART” (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) operationalisation and capacity gaps.

Habitat III – a vehicle for SDG implementation?

Even more importantly, the task of concretising the urban governance dimension – and thereby easing SDG implementation – must also be related to other global policy processes and events. Notably the New Urban Agenda (NUA) of the third UN-Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) should be considered a key vehicle in this regard.

Against the background of the aforementioned urban governance gaps and the relevance of cities beyond Goal 11 for successfully implementing the SDGs, it seems clearly pertinent to connect Agenda 2030 and the NUA. Such a linkage is also likely to enhance the influence of urban stakeholders, particularly local governments, in persistently nation-state-centric UN processes. Hence, the NUA should specify urban governance-related policy recommendations and related indicators in the following decisive areas:

Context-specific urban frameworks: Although country-specific particularities need to be considered, national (urban) policy frameworks and corresponding fiscal and financial regulations must define local and urban functions and responsibilities. Additionally, the multilevel management of new and highly dynamic urban forms such as metropolitan areas and urban corridors must be regulated.

(Intra-)Urban participation and partnerships: New collaboration spaces and partnerships between governments, academia, the private sector and increasingly fluid local communities must be sought out to produce equitable outcomes and adaptive capacities.

Transformative governance: Mechanisms to enable city- or metropolitan-scale climate action must be sought out. Additionally, strategies must be designed in such a way to include and protect the most disadvantaged urban groups.

“Transforming our World” – this is the vision that Agenda 2030 set off with. To be truly transformative, the role of urban governance with regards to the SDGs needs to be further elaborated. Besides complementary indicator formulations, the NUA can make crucial contributions towards this aim.