Rethinking “Fortress Europe”: Public Spaces from Idomeni to Thessaloniki, Greece

After years of ongoing crisis, the once called temporary measures at the EU borders have become constant ones: the Fortress Europe has solidified. Isabell Enssle presents the effects the fortified border has for communities and public spaces from the North Macedonian-Greek borderline to the city of Thessaloniki, linking them with a tool kit for inclusive public spaces.

Border Constructions and Militarisation of the Border Spaces

When we hear about border constructions, we think about the wall between Israel and Palestine, the US-Mexico fence, or the fortified barriers between North and South Korea. But we often do not realise that physical barriers were also built on European Union (EU) territory.

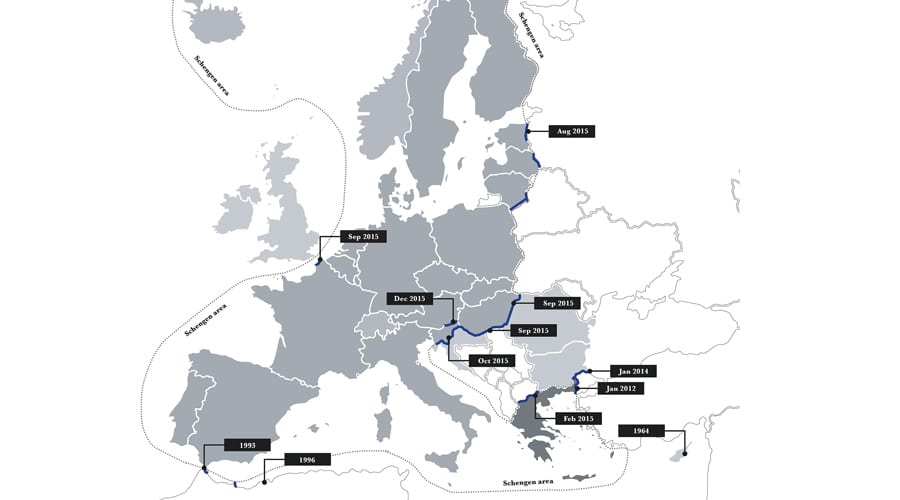

The state borders of most European countries started to be heavily controlled and closed when increased numbers of refugees and migrants started to arrive from 2012 onwards. While some European borders have been walled for decades – such as the Spanish enclaves Melilla and Ceuta in Morocco – the newly constructed walls were located within EU territory. The fence along the border between Greece and Turkey, in 2012, was the first one to be constructed. Since 2015, other EU countries have followed, and many new fences have been constructed, among others in Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovenia, the Republic of North Macedonia, and Austria.

Those border fences have been built inside the Schengen area and are thus impeding the freedom of movement among EU states, built to fortify Europe’s borders and to ward off migration from the Global South to ensure Western prosperity and values.

Border fences in Europe, January 2019 © UNHCR, 2017, edited by author

At present, the EU places all the responsibility on Spain, Italy, and Greece due to their geographical position on the Mediterranean Sea and the fact that, under EU law, asylum seekers must lodge their applications in the first EU country they enter. However, most of the people hope to find a way to wealthier northern European states. But since the construction of the new fortified borders in the Balkans, the border towns in Greece, Italy, and Spain have become the terminal of their journeys. The border areas, turned into military spaces monitored by cameras and soldiers, started shifting more towards the inside of their countries, aiming to stop people before they even reach the political border.

Border fence © bordermonitoring.eu

Diffuse Borders from Idomeni to Thessaloniki

In March 2016, the Republic of North Macedonia closed its border “temporarily” to control the migration flow. Idomeni, a little Greek border village was noted around the world: when the refugee route through the Balkans got closed, migrants suddenly were stranded, and makeshift camps appeared. Thousands of migrants were waiting, demonstrating for the possibility to cross the border. After evicting people from the makeshift camps into official camps provided by the state, the border shifted towards the suburbs, the official camps for asylum seekers, and the city centre of Thessaloniki.

“You can’t evict movement” © bordermonitoring.eu

Today the border in the Idomeni region in Greece is still closed and the temporary application became a permanent one. The Fortress Europe has solidified. The border zone itself became a dangerous edge, neglected by the Greek community, controlled by smuggler groups and the mafia of the Republic of North Macedonia. This is happening with the continuing absence of the Greek state and an observed increase in interference from the European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex.

Protest in Idomeni © bordermonitoring.eu

Successive Crises and Segregationist Planning Policies

To put such burden on Greece as a terminal country leads to several unjust consequences. The EU’s urban planning policies for refugee accommodation enforces territorial separation between host and migrant communities and is running the risk to establish an segregationist, racist system in Greece.

Despite the mostly welcoming initial reactions of the host community, Greece is suffering from socio-economic instability, and it is expected that the tensions between host and refugee communities will grow. Furhermore, the described border shift from Idomeni to Thessaloniki increases the spatial and social segregation of the refugee and host communities.

The situation in Greek refugee camps remains very bad, and for many people there is no prospect of being granted asylum. With the Covid-19 pandemic, the situation in the camps has worsened. Greece has been trying to contain refugees and migrants by transforming their accommodations into closed camps.

For recognised refugees as well, the living conditions became devastating when the housing program “Filoxenia” ended while the economic and labour market in Greece remains unstable. Given the situation, its location, and current political attitudes of the EU, the Idomeni region will likely continue to receive significant numbers of refugees in the upcoming years. Therefore, it urgently demands a more humane solution and integrated planning solution.

Inclusive Public Spaces

It is imperative to change perspective and to see migrants and refugees not as burden, but as potential for Greece. This entails perceiving refugee camps and accommodations as places that have to be connected to their surroundings, instead of being isolated communities. The significance of inclusive and accessible social spaces and leisure activities should also be kept in mind, including those that allow refugees to develop and share skills, regardless of their intention to leave or remain in the city.

Current political regulations and urban limitations cannot be changed easily, but we can initiate urban processes to influence future political decisions. The change can start in the public space as catalyst to build a sense of shared culture and to overcome the new shifted borders.

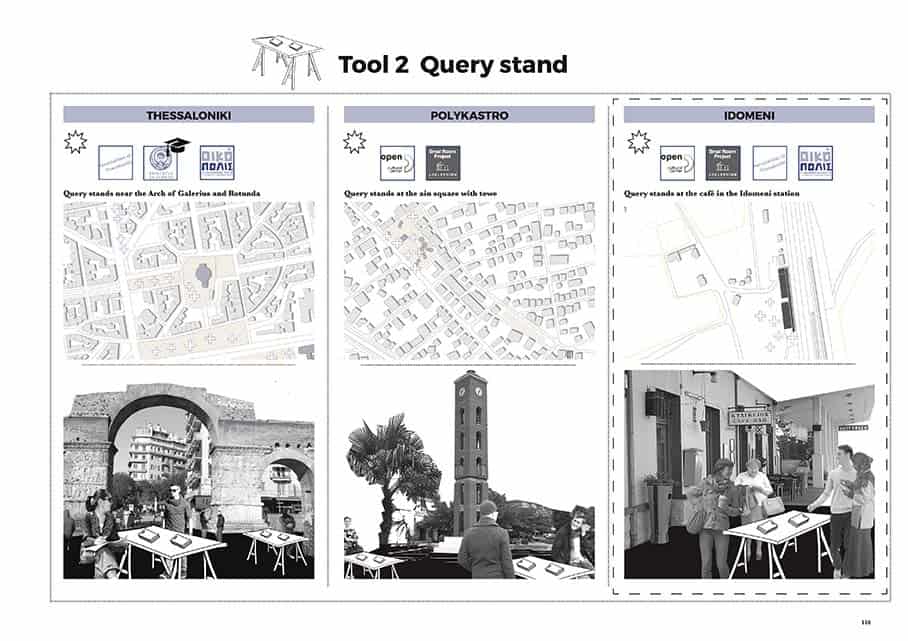

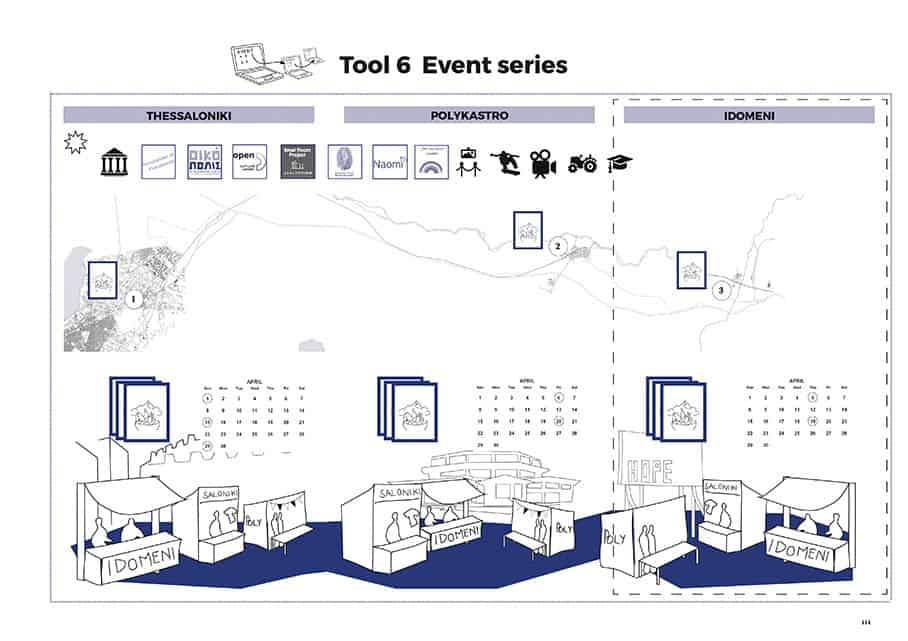

Therefore, a strategy is proposed that includes a tool kit to foster inclusive public spaces. The focus is on public spaces like parks, squares, streets, infrastructure, and vacant land, but also on public buildings and the use of empty shops on ground floor levels. The strategic tool kit is not intended to be a solution for the overall issue analysed above, but rather a catalogue for implementation possibilities.

Tool Kit for inclusive public spaces © Isabell Enssle

Tool Kit for inclusive public spaces © Isabell Enssle

The catalogue shows instruments for intervention into public space, aiming for a gradual improvement of migrants’ life situation in the case study region. All of the proposed tools are sensitive, minor interventions that can be applied with a low budget. The first steps propose making urban planning temporary and flexible. Urban development in Greece has slowed down due to economic crisis and the collapse of the property market, resulting in the neglection of public spaces and a high vacancy rate. The abandoned places and residual areas provide potential for temporary use, and thus to fill the time gap before new development is initiated.

It is essential to combine the integration of refugees and the emergence of urban experiments in time of crisis, creating a key trigger for urban development. We need to rethink how initiatives can be formed, mobilised, or reactivated in order to create cross-border public spaces. The attempt is to create spatial connections that will encourage social connections, and to form social relations that will encourage spatial relations.