Resilient Cities are Green Cities

COVID-19 has strengthened our understanding of the vital relationship between healthy environments and the need for sustainable infrastructure. Donovan Storey from the Global Green Growth Institute reminds us that it is precisely in times of crises that we should commit to more holistic and ambitious green transformations.

Cities are on the frontlines of the current COVID-19 pandemic – and the crisis has exposed the consequences of persistent urban inequalities and development gaps, including access to healthy homes and environments. As such, the pandemic is reinforcing, once again, the urgent need to invest in the transition to a low carbon and sustainable urban future. And yet it has paradoxically challenged the very same key norms that underpin this transition.

COVID-19, and the responses to it, have significantly disrupted planning and investing in compact and connected cities, and in mass public transport systems. It has also interrupted both infrastructure and supply chains supporting the shift to waste-to-resource and circular economies. In light of the spatial and behavioural shocks of COVID-19, we need to reassess and recommit to these ‘pillars’ of connected, compact, and clean cities.

Good Density, Bad Density

Indeed, COVID-19 has reignited a very important debate on the pros and cons of density and urban design. People are now seeking to flee compact urban areas and feel ‘locked-in’ and vulnerable where they cannot. Dense cities are suddenly associated not with the benefits of access and proximity, but with contagious environments in which especially the vulnerable and poor are unable to isolate themselves. Governor Cuomo of New York, for example, has claimed an association between density and the pandemic’s impact, even though other densely populated cities, such as Tokyo, Taipei and Seoul, have fared comparatively well. Yet, health concerns over our dense and interconnected urban life are currently evident in many countries.

But how can we support ‘good’ density, in the form of healthy and green density, as goals now critical to achieving low carbon, efficient and connected cities? How can we then avoid ‘bad’ density, particularly relating to the continued shelter crisis in the developing world, where density has not been accompanied by access to services and adequate water and sanitation infrastructure?

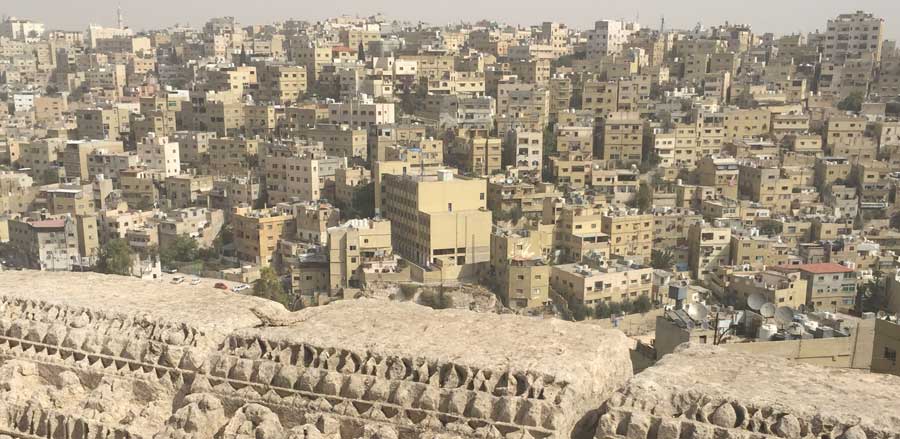

Density in Amman, Jordan © Donovan Storey

Green Spaces as Public Health Assets

Density is primarily a means to an end. It should support quality of life outcomes, linked to innovative design which supports both dense and healthy environments. To date, this ‘soft infrastructure’ has been a weaker element of the green city agenda, which must now be urgently mainstreamed.

In that respect, public and green spaces have been shown to be an essential physical asset for well-being in cities, linked to better mental and physical health of residents, and a variety of ecological benefits. To date, however, green spaces have been lost in cities through lack of ‘bankability’. Too much green space and biodiversity has been destroyed through land conversion and poor management. In Thailand, for instance, communities and conservationists have been battling for years to save one of Bangkok’s last and largest remaining green spaces from being developed into yet another shopping mall.

Yet the current crisis demonstrates that public green spaces are invaluable – as social, environmental, and economic resources. Integrating green spaces into urban planning, as essential assets for healthy and sustainable cities, must be placed more firmly on urban planning agendas. Investing in ecological systems not only provides benefits in urban well-being but also offers critical buffers against other natural disasters and the impacts of climate change. Green spaces are essential to urban resilience more broadly, and their co-benefits now much more evident.

Best Practices for Healthier Cities

South Korea’s capital sets a positive example in this regard. The Seoul Metropolitan Government has recently announced the ‘Seoul Green New Deal’ policy, starting in 2020. Through this, Seoul is integrating quality of life initiatives with climate ambitions, for example, by strictly limiting greenhouse gas emissions from public buildings, increasing the number of pedestrian walkways, and strengthening green mobility including bike-sharing.

In the developing world, green spaces are also gaining greater traction as critical assets to healthy, resilient, and inclusive cities. Rwanda, for example, has recently identified gaps in a common definition and regulatory approach to ‘public spaces’. Public and green spaces are to be recognised as development priorities, especially with respect to climate adaptation, disaster-risk resilience, biodiversity, and public health. Investment in public environmental goods is therefore seen as important as economic recovery, and as such to a balanced recovery from COVID-19.

Kigali, Rwanda © Donovan Storey

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged many of the key norms that underpin our transition to more climate-resilient, sustainable and prosperous urban futures. If we, however, grasp this opportunity to re-focus on the development of healthier urban spaces, we can re-shape urban and regional planning to further green the sustainable urban agenda for generations to come. Now is the time to ‘lock-in’ the urgent policy and investment shifts needed for this transition. Accessible green public space in support of healthy density has a critical role to play in that future.

- Resilient Cities are Green Cities - 2. July 2020

- Circular Economies as an Answer to the Waste Crisis: Lessons Learnt - 21. April 2020