National Urban Policies: a policy lever to foster a New Urban Agenda? – Part II

By Rene Peter Hohmann

The New Urban Agenda calls upon nation states to implement National Urban Policies to achieve integrated and coherent sustainable urban development. In the first part of this article, author Rene Peter Hohmann displays current discussions on National Urban Policies and their possible categorisation as this question remains open. To reflect on the various policy intentions that national governments may pursue under an umbrella of National Urban Policies, this second part will examine a variety of case studies more closely.

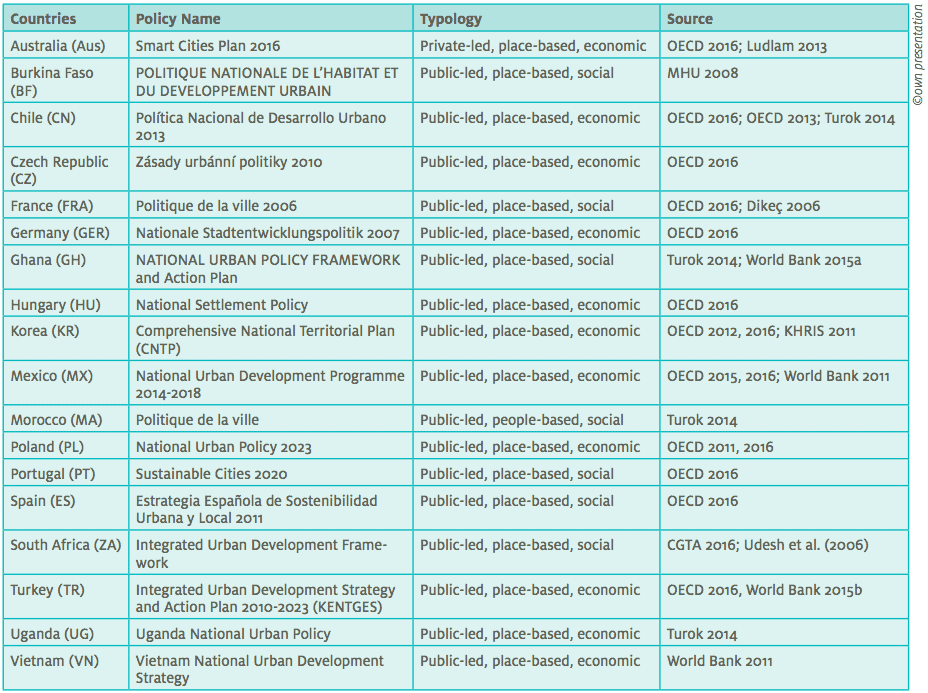

The body of existing literature providing a comparative review of National Urban Policies (NUP) can be considered as rather thin. Despite the lack of comparative works on NUP, the literature on single country reviews has increased in recent years, especially through the initiative of multilateral organisations, such as the World Bank and the OECD. Based on this combined body of country-level reviews, a first analysis of the policy contents and typologies of NUPs can be undertaken. For this exercise, a sample of 19 countries with an explicit NUP has been chosen to apply the categorisation as introduced in the previous article. Table 1 below provides an overview of the countries reviewed, and categorises their respective NUPs according to the presented typology.

Table 1: Sample of Countries with an explicit National Urban Policy

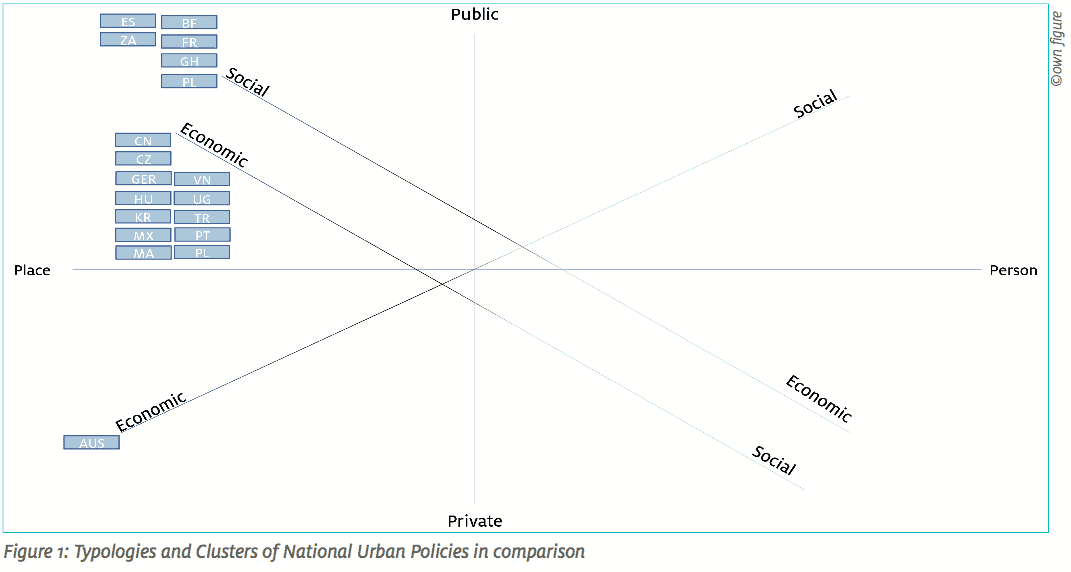

Mapping those policies to the policy continua produces two distinct clusters of typologies as shown in Figure 1 below.

Cluster I combines all National Urban Policies that are primarily formulated for government agencies to implement a set of initiatives in cities to foster social cohesion and inclusion. Cluster II encompasses economically driven initiatives that aim to provide a conducive economic environment by state agencies in cities. Australia with its clear focus on private sector entities to drive economic development in cities appears to be an exceptional case.

It should be noted that most NUPs have combined various, sometimes conflicting elements in their policy. In this sense, they can indeed be considered as situated on at least one policy continua between two opposite objectives.

Key observations from the analysis

This mapping exercise allows already to formulate three key observations.

Firstly, the majority of NUPs in the sample considers the state and government institutions as primary change agents for the implementation of urban policy, despite the differences between the countries’ own political system and constitutional circumstances. While the objectives may differ between more socially or economically driven motives, NUPs can predominantly be conceived as a policy vehicle for improved planning and service delivery by the state. This is clearly in line with the ambitions of the New Urban Agenda and its recognition for “the leading role of national Governments, as appropriate, in the definition and implementation of inclusive and effective urban policies and legislation for sustainable urban development, and the equally important contributions of subnational and local governments, as well as civil society and other relevant stakeholders, in a transparent and accountable manner.” (UNGA 2017: 6)

Secondly and related to the observation above, is the lack of NUP examples that are distinctly people-based in the formulation and implementation of the policy. It has to be acknowledged that due to their orientation to social development issues, Cluster I NUPs foster for example area-based initiatives addressing socio-economic inequalities. However, the absence in this sample of explicitly people-centred NUPs may pose a significant hurdle to the New Urban Agenda’s aim to “adopt sustainable, people-centred, age- and gender-responsive and integrated approaches to urban and territorial development.” (UNGA 2017: 5)

Thirdly this conceptual lens could be further strengthened through broadening of categories, not at least through adding environmental policies as a characteristic feature of many contemporary NUPs.

Potential pitfalls in promoting the New Urban Agenda through National Urban Policies

Mapping the policy contents of existing National Urban Policies has shown that these policies are primarily based on state-driven development interventions fostering either more social or economic development objectives. Since the New Urban Agenda has not generated a distinct action plan with specific outcome indicators, a basic complementarity of the major intentions of the New Urban Agenda with existing policy contents of National Urban Policies can be confirmed. However, reflecting upon the developments in the emerging field of action around NUPs, at least two potential pitfalls can be formulated.

Pitfall 1: National Urban Policies are conducive but not sufficient to achieve sustainable cities.

One of the most politically sensitive issues could be seen in the question whether an urban policy should be situated at the national level or at other tiers of government that may be closer and effective to formulate and implement these policies.

A qualitative benchmark assessment undertaken by UCLG Africa on 50 African countries considers National Urban Strategies as only one out of 10 criteria restricting or enhancing the capacity of local governments to act. It is however noteworthy that the results of these assessment also indicate that those countries with some of the most conducive national institutional enabling environments for local governments to act, such as South Africa, Uganda, Morocco, are also considered to have NUPs formulated. At the same time, there are countries, such as Egypt, Ethiopia and Malawi that have NUPS in place but are considered as countries with a rather restrictive institutional enabling environment for cities and their governments to act.

It points to the fact that if NUPs are considered to be a distinct feature in the New Urban Agenda, these policies need to be sharply differentiated from those reform initiatives that are constitutionally, legally and financially influencing the capacity of local authorities.

Pitfall 2: A prescriptive global National Urban Policy template may turn out to be harmful to local innovation.

In a more interconnected world, in which ideas and fashions are accelerated through the use of new technologies and global platforms for exchange, the growing field of research on policy mobilities could be considered as a very important concept to better understand the consequences and potential pitfalls of international agreements, such as the New Urban Agenda. Policy makers and development partners may need to be aware of the pitfalls of promoting ‘silver bullet’ solutions to avoid jeopardising the creation of local policy innovations that are more suitable to national and local contexts.

An example on the challenges of such fast policies can be found in the review on the popularity and transnational promotion of conditional cash transfers, a policy that promotes social transfer payments upon behavioural compliance of recipients. Similar fast travelling policies, which have been critically assessed, is the concept of Creative Cities or Smart Cities as well as “mass scaled supply-driven approaches to housing provision” in Africa.

Given that National Urban Policies are based on a very broad definition and indeed can only be broadly characterised, there is an inherent danger of prescribing a global policy template of what National Urban Policies should be composed of, especially in those countries that have not yet formulated a response to urbanisation and sustainable urban development. Caution may therefore be called upon any global trends to formulate toolkits, guidelines and other forms of advice promoted by primarily development partners in response to the review and follow-up of the New Urban Agenda and specifically in support of National Urban Policies as a potential policy lever for its implementation at the national level.