Making a world without HIV by 2030 possible: Mayors and local governments as change agents

By Titus James Twesige

HIV/AIDS continues to be a major health crisis around the world, especially in cities. As part of the Sustainable Development Goals, the Alliance of Mayors and Municipal Leaders on HIV/AIDS in Africa has vouched to eliminate AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. Titus James Twesige explains the situation in Uganda and why mayors can drive positive change.

The global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are encouraging us to make “the world we want” with an all-inclusive, participatory, people-centered sustainable development approach. In line with this, the Alliance of Mayors and Municipal Leaders on HIV/AIDS in Africa (AMICAALL) strives to ensure good health and wellbeing (SDG 3) and through the global Fast Track HIV and AIDS Initiative, [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”URBANET” suffix=””]achieve elimination of AIDS as a public health threat by 2030[/inlinetweet]. However, these will simply remain utopian and wishful thinking, unless realistic and practical mechanisms to achieve them are put in place.

Decentralisation in Uganda

When Uganda adopted its decentralisation policy in the early 1990s, Ugandans welcomed the idea of devolution of power, responsibility and development with the hope that it would foster fast, equitable and people-driven local development. District and municipality local governments were to be at the frontline of service delivery. Elected leaders right from the village (Local Council 1), through parishes (Local Council II), sub-counties (Local Councils III), counties (Parliamentary Constituencies) to districts (Local Council V) were meant to ensure that communities are sensitised, consulted and meaningfully represented, mobilised and involved in making decisions that allocate and manage resources to address their local challenges.

But despite a smart decentralisation policy now in place, most local governments have remained with false autonomy. They are heavily dependent on central government conditional grants with very limited or no self-management capacity.

Urban areas have highest HIV and AIDS rates

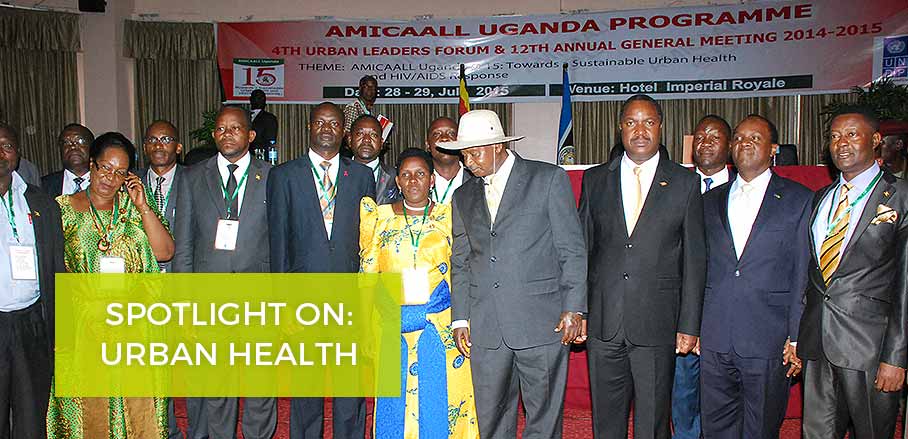

The country also adopted a multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder HIV and AIDS response aligned to the decentralised structure. In the early 1990s, Uganda’s acclaimed model of success in combating HIV and AIDS was largely attributed to the strong political leadership commitment, particularly spearheaded by President Yoweri Museveni. However, the extent to which the leadership at the top has been emulated and cascaded downwards to where people get infected leaves a lot to be desired. When leaders ascend to their leadership positions, they are either unaware of what they need to do, or they lack the commitment or the skills and resources necessary to effectively combat HIV/AIDS in their communities.

During the 1997 International AIDS Conference on AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infections in Africa (ICASA) in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire it became very clear that [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”URBANET” suffix=””]urban areas bear the biggest burden of the AIDS epidemic[/inlinetweet] and that they continue to be the epicenters for its spread. In Uganda for example, urban HIV prevalence statistics have been consistently higher in urban areas since 2005 (10.1%) through 2011 (8.3%) until 2016 (7.1%), compared to HIV prevalence in rural areas (5.7%, 7.0%, and 5.5%) and the general population (6.4%, 7.3%, 6.0%)[1]Trends of HIV prevalence as reported in the Uganda AIDS Indicator Surveys 2005, 2011 and 2016 by the Uganda AIDS Commission. . The country’s annual urbanisation rate is high at 5.2-5.9% and is steadily increasing. Currently, Uganda has five city divisions, 41 municipalities, and 186 town councils[2]Draft Uganda National Urban Policy (2016). Yet, under Vision 2040[3]http://npa.ug/uganda-vision-2040/, there are plans to gazette more municipalities, town councils and up to ten cities as centers for growth towards attainment of middle-income status by 2020.

It was in light of the high HIV prevalence rates in urban settings that African Mayors and other urban leaders came together to form AMICAALL. The goal of the Alliance is to promote and support concrete actions that contribute towards limiting the spread of HIV and alleviating the social and economic impact of the epidemic at the local level. It brings together key local government and community leaders, and provides them with an opportunity to articulate their realities and invest in developing their capacities to manage and facilitate an expanded, multi-sectoral response to the growing challenges of HIV and AIDS in their cities, municipalities and towns.

The role of mayors as change agents

Since the inauguration of the AMICAALL Uganda chapter in the year 2000, Ugandan Mayors have demonstrated the potential to spearhead a cost-effective, impactful and sustainable decentralised urban response to HIV and AIDS. The dual mandate of mayors as local government representatives and as civic leaders puts them in a unique position. People trust and believe in them, and are therefore likely to listen to their advice and be inspired by their actions. Mayors are often called upon to speak to people at various congregations including in churches, in mosques, at funerals and wedding functions, political gatherings, or on mass media platforms. When not prepared with a message on HIV prevention or control, mayors may end up making political speeches rather than talking about urgent issues that affect the daily lives of the people they represent.

Therefore, when well educated and equipped with the right messages, mayors have demonstrated passion and proved to be major change agents within their communities. They mobilise communities to come out and use available HIV prevention services like HIV testing, especially when they lead by example. They have put in place byelaws and ordinances that provide a conducive and supportive environment to key population groups which are marginalized and repressed by national laws such as sex workers, men who have sex with men, and drug users to access health services. Some mayors have put in place HIV prevention plans in their municipalities and mobilised local civil society, the private sector, donor partners and even public health facilities to provide resources and services for the implementation of these plans.

For example, through the annual mayors’ campaign organised by AMICAALL Uganda Chapter, mayors have been able to mobilise stakeholders, including civil society organisations, implementing partners, private clinics and government health facilities to ensure accelerated service delivery through community outreach. They have effectively supervised the technical teams of civil servants, monitored programmes and ensured equity and accountability to their communities by presenting financial and programme accountability reports. In mutual support and solidarity formed through AMICAALL Uganda chapter, mayors have advocated to the central government, parliament and donors on policy issues relating to health services to effectively combat HIV and AIDS. With solidarity among mayors and other urban leaders, there is hope for a future without HIV and AIDS.