Localising the SDGs: A Call for Urban Equality as a Guiding Principle

Localising the global Sustainable Development Goals presents key challenges to policymakers everywhere. An ‘Urban Equality lens’ however, may help navigate some of the tensions, contradictions, and gaps in the Agenda. By KNOW Investigators.

In Dar es Salaam, the Centre for Community Initiatives (CCI), in partnership with the Tanzanian Urban Poor Federation, has revealed the impact and scale of poor sanitation through the mapping and profiling of informal settlements. Together they are developing and implementing affordable solutions with local communities like the simplified sewerage system in Vingunguti, integrating it into city sanitation facilities and partnering with local government and utilities to scale up across the city. What can such local and innovative actions to address urban inequalities teach us about achieving the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

SDG localisation is an opportunity for transformative global action on one of our most pressing challenges: urban inequality. The urgency to do so is recognised in goals to “reduce inequality” (10) and achieve “sustainable cities and communities” (11). Crucially, the rallying cry to “leave no person and no place behind” demands action on the most complex drivers of deprivation – and the recognition of how vulnerabilities intersect with gender, class, religion, ethnicity, race, age, ability, among other social identities.

The urbanisation of inequalities has only been exacerbated by the pandemic – with more than 95 per cent of COVID-19 cases in urban areas – unequally distributed and experienced by different groups within and between diverse urban contexts. How can an ‘Urban Equality lens’ guide the realisation of the SDG?

SDG localisation presents key challenges for city administrations, policymakers and civil society at different levels. The Goals represent a political consensus, reflecting diverse priorities and understandings of contested concepts such as ‘sustainability’ and ‘resilience’. These differences will sharpen as decisions about how to develop policy and distribute resources are made. We argue this lens can act as an orientation to inform decision-making, and to navigate some of the tensions, contradictions, and gaps in the Agenda.

Why Adopt an Urban Equality Lens?

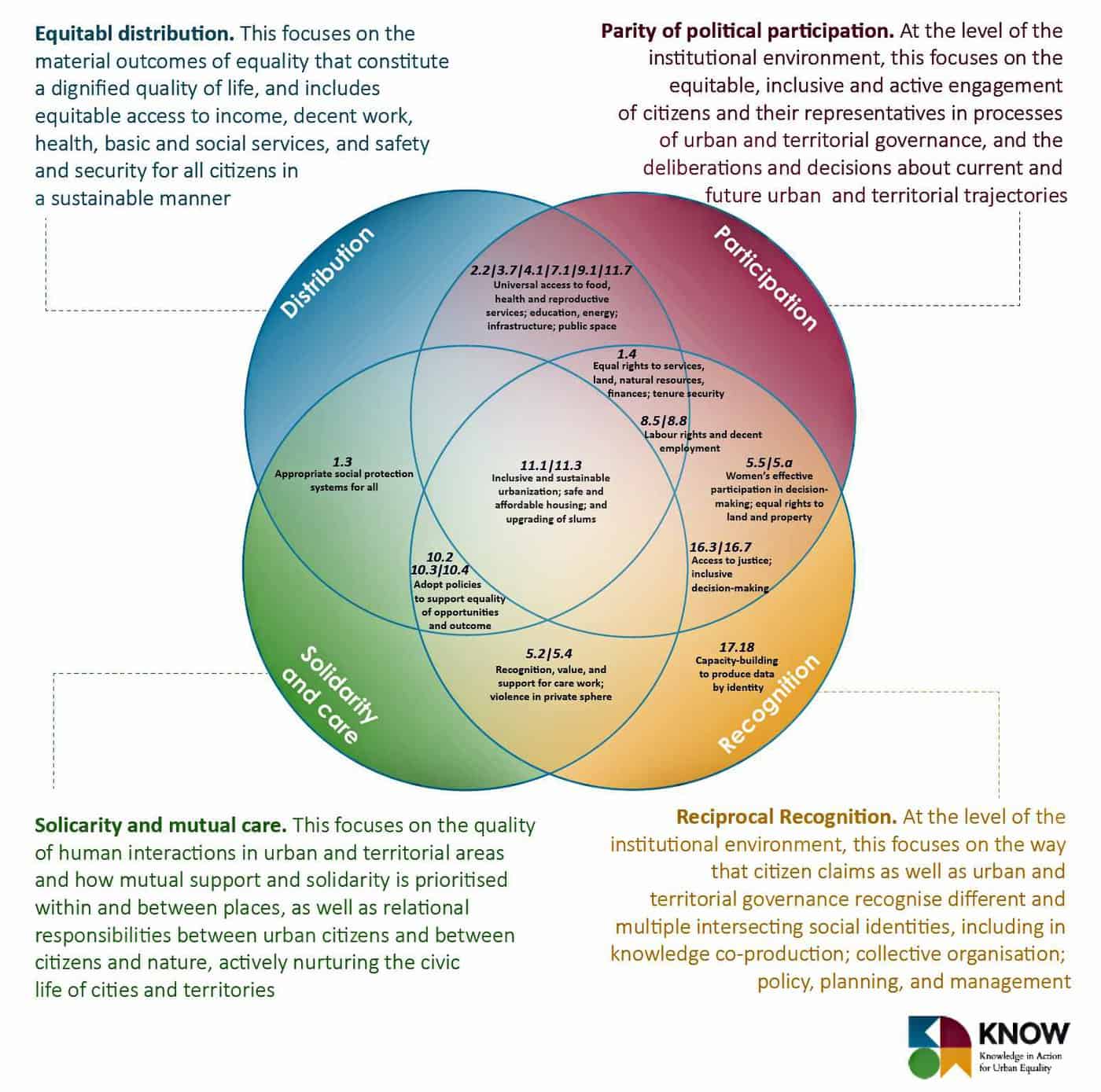

We understand Urban Equality (UE) to include four interrelated dimensions: equitable distribution; reciprocal recognition; parity of political participation; and solidarity and mutual care (Figure 1). We argue that a UE lens offers at least three useful perspectives for localisation.

It can guide decision-making through potential synergies and tensions – i.e. tensions between economic growth (Goal 8) and climate action (Goal 13) – towards more holistic just and sustainable interventions. Given the challenges of interpreting and actioning a universal agenda within diverse and specific local contexts, a UE lens can support local monitoring and measurement across diverse contexts, emphasising that the process through which targets are locally interpreted and measured, is as important as their outcomes. A UE lens can also deepen the inclusion aspects of the Agenda – drawing attention to the broader structures and urban processes which have generated social and spatial injustices over time.

Figure 1: Locating urban equality outcomes in the SDGs within KNOW dimensions. Based on Butcher et al., 2021

As a part of ongoing work within the Knowledge in Action for Urban Equality programme (KNOW), we have examined the multi-dimensional and interlinked dimensions of UE, with partners in cities across Africa, Asia and Latin America. In a recent report, we discuss KNOW partners’ experiences in co-producing knowledge towards urban equality, and lessons for localising the SDGs. For instance, the Asian Coalition of Housing Rights has long challenged the notion of land as an individual economic asset, through community savings and loans schemes, and collective forms of tenure.

In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, the (CCI) has developed community indicators of ‘prosperity’, revealing crucial but often unrecognised dimensions such as power and voice. Or, the work of the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, NGOs and the Freetown City Council in developing a City Learning Platform in Freetown, has demonstrated how “inclusive, participatory decision-making” (target 11.7) might be realised in practice, involving diverse urban actors.

Four Principles for SDG Localisation

From these diverse grounded activities, we argue that a focus on UE must inform SDG localisation as a way to respond to the urgency of the SDGs and to challenge injustices. Our UE lens suggests four principles for SDG localisation:

1. Deeper attention to the political economy of the city: recognising that important distributional aims cannot be achieved without also addressing trends such as the commodification of land and housing, privatisation of services, or the precarity of labour conditions.

2. Engaging in solidarity to nurture the civic life of the city: drawing attention to missing dimensions in the SDGs such as self-determination, belonging, equilibrium with nature, or confidence. Solidarity and mutual care are often strongly articulated through lived experiences, particularly the struggles of excluded groups, and must not be forgotten.

3. Nurturing partnerships and collective decision-making across sectors and with diverse stakeholders: leveraging targets linked with participation in planning, governance, and the management of services, while actively centring voices that historically have been marginalised, to support a deeper parity of participation.

4. Recognising relations of power in the analysis, development and monitoring of strategies to meet the SDGs: recognition of the aspirations, knowledge, and priorities of diverse urban poor groups in the negotiation of trade-offs and contradictions of the agenda, requiring grounded methodologies to articulate locally- relevant visions, measurements, and approaches.

Drawing on these principles, we believe that the notion of UE can productively guide SDG localisation to navigate possible tensions between Goals, deepen engagement with diverse and specific local contexts, and orient policy programmes and action towards truly inclusive, just and equal urban futures.