Environmental Justice: Making a Case for Sustainable and Equitable Urban Mobility in Abuja

Can Abuja’s urban mobility guarantee a sustainable and equitable future? Mathias Agbo Jr. spotlights the transformative potentials of projects like the Abuja Light Rail, reimagined Urban Mass Transit, pedestrian pathways, and cycling initiatives. Discover how these innovations could offer a greener, more equitable city.

Sustainable mobility contributes to strengthening a society’s adaptive capacity to the impacts of climate change by reducing the environmental impact of the transport sector and improving the resilience of transport infrastructure. This is crucial as the transport sector plays a significant role in climate change adaptation.

Abuja, the capital city of Nigeria, for example, stands on the precipice of an uncertain future, driven by its rapid population growth. Encircling the city lie several satellite towns, such as Gwagwalada, Bwari, Kuje, Maraba, and Karshi, that were originally intended to be homes for the working-class and low-income earners. The idea was to facilitate daily commutes for people who work in the city centre. However, mainly due to the lack of a functional urban mobility network, the planned spatial arrangement in these settlements has not been successful. As a result, residents are left with no choice but to rely on private cars and taxis. This reliance is worsening the growing traffic congestion and exposing residents to high amounts of ambient carbon dioxide daily.

Socio-economically, the absence of affordable mass transit services in Abuja translates to the city’s underpaid working class spending a substantial part of their meagre income on transportation, leaving very little for essential needs like food. This reality significantly contributes to the growing chasm between the city’s rich and poor.

This situation has been further exacerbated by the recent removal of petroleum subsidies, resulting in a staggering 200 per cent hike in petrol costs. To avoid the high cost and inconvenience of commuting to and from the city centre, many of Abuja’s low-income earners have chosen to live near the city at all costs. These decisions have created a landscape of makeshift shelters and illegal settlements in the city’s surroundings. Consequently, the increasing number of people living in these makeshift communities puts a significant strain on the city’s already limited public amenities.

Tragically, many of these illegal settlements are regularly demolished by city authorities, leaving their inhabitants without a home. This has resulted in severe spatial fragmentation, reinforcing social inequality throughout the city, and aggravating the growing social tensions between the affluent and the poor.

Sustainable Mobility as a Pathway to Environmental Justice

Urban mobility plays a vital role in ensuring environmental and social justice in modern cities. At its core lies the imperative of equitable distribution of transportation and ensuring access to local destinations and shared services. The fair allocation of transportation resources and accessibility to local amenities is a crucial benchmark for evaluating the effectiveness of government policies in any city. One of the most visible indicators of spatial inequality in contemporary cities is unequal access to urban mobility.

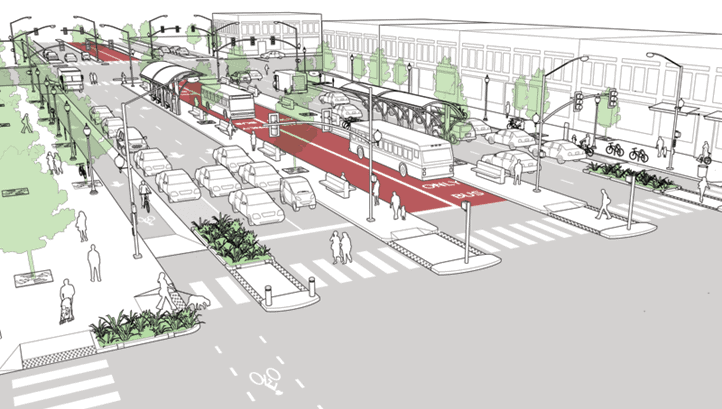

Creating a sustainable and equitable mobility system is crucial for any city. Picture this: an integrated, sustainable multi-modal transport system that significantly reduces the number of private cars on the road and seamlessly citizens at different levels, with options to alternate between transport modes as needed.

The prototype of the equitable multi-modal Urban Mobility Network © NACTO

This vision materialises through the proposed mobility network that will integrate light rail systems, Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) lanes, bicycle lanes, and pedestrian pathways, all laid out in proximity and overlapping with each other to ensure a seamless connection.

Abuja’s Light Rail Network: A Renewed Path to Urban Mobility

One tangible step towards this vision was taken in 2018 when the city authorities of Abuja launched a 42.5 km intra-city passenger rail system. Consisting of two lines and 12 stations, this was the first instalment of a planned 290 km network that was to be developed in six phases, Lots 1-6.

However, despite a promising start, passenger service on these lines was suspended in 2020 for unstated operational reasons. Simultaneously, progress on the construction work on the other lines ceased abruptly a few years ago over funding and contractual disputes. The photo below shows the master plan proposed for Abuja Light Rail, which now awaits a renewed trajectory.

This is the existing masterplan for Abuja’s Light Rail Network © FCDA, Abuja

Once completed, the potential impact of this project promises to significantly improve the mobility of Abuja’s working class by moving more people to and from the city centre quicker and cheaper, while considerably reducing the number of cars on the roads. A report by the US General Accounting Office (GAO) estimates that each passenger train along the Los Angeles-San Diego route kept at least 129 cars off the roads, and an overall total of 2,240 cars each day, highlighting the transformative power of the passenger rail system.

Abuja’s Urban Mass Transit Reimagined: The BRT Solution

Shifting the focus back to the Abuja Urban Mass Transit service, it commenced operations with over 500 high-capacity and large 49-seat buses. Yet, after a few years, it has become moribund, due to maladministration. The prospect of rejuvenating it as a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) service, with a dedicated lane holds promise to be a game changer in addressing issues of equality in urban mobility.

By seamlessly integrating the BRT system with other mobility options, Abuja can create a comprehensive low-cost mobility solution that has the potential to address equity issues by providing affordable and equitable access to urban spaces.

According to Bogotá’s mayor, Enrique Peñalosa, TransMilenio – Bogotá’s BRT system, has contributed the most to improving the quality of life of its citizens since its implementation in 2000, providing an all-inclusive, low-cost mobility option that provides equal access to all parts of the city.

Making Abuja Walkable: A Vision for Safe Urban Mobility

Nevertheless, Abuja is faced with severe environmental inequality, particularly in terms of pedestrian accessibility. Most of its roads have narrow or no sidewalks, making it difficult for two people to walk in opposite directions at the same time. This lack of proper pedestrian pathways makes even short distances unwalkable, putting pedestrians at risk of accidents from vehicles encroaching on pedestrian pathways.

Therefore, building pedestrian pathways like paved sidewalks, zebra crossings, and pedestrian bridges across the city, would make walking safer and more appealing to the residents. Additionally, there should be a few strategically located pedestrian-only streets in the city centre and Central Business District (CBD), where most government offices are clustered within walking distance of each other. These measures collectively address the critical issue of pedestrian accessibility, ushering in a safer and more inviting urban mobility landscape for Abuja’s inhabitants.

Abuja’s Cycling Campaign: Lessons for the Future

In 2001, Nigeria’s Ministry of Transport launched a national campaign promoting bicycle mobility with Abuja as a pilot city. However, this promising campaign was regrettably short-lived, falling victim to an unfortunate incident involving the campaign’s chief proponent, the then Minister of Transport, Ojo Maduekwe. On his way to work, Maduekwe was knocked off his bicycle by a bus. This unfortunate incident highlights a critical issue: the absence of dedicated bicycle lanes, making cycling a risky and unsafe venture for residents, and stands as a major reason for the campaign’s failure.

The solution lies in the establishment of dedicated bicycle lanes, stacking sheds, and incentives that will encourage residents to cycle more, promoting last-mile mobility between LRT stations, BRT bus stops, and pedestrian pathways. This inclusive urban mobility framework ensures that mobility is accessible to all and promotes a greater sense of environmental and social justice.

Abuja, Nigeria’s capital stands at a crossroads shaped by rapid population growth, financial strains on the working class, as well as social and environmental inequalities.