At COP26, Cities were Climate Action Watchdogs

Lou Del Bello reports on COP26, the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference that took place in Glasgow, Scotland.

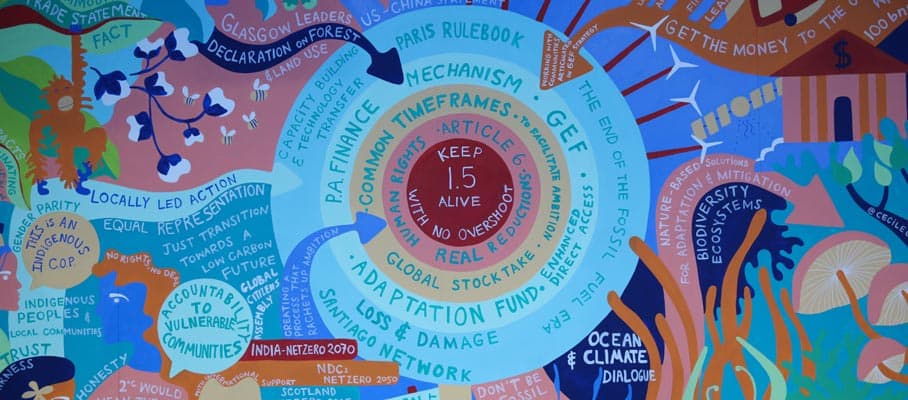

The Glasgow Climate Pact

The Glasgow Climate Pact, approved in overtime on Saturday afternoon, marked the conclusion of two weeks of tense negotiations at COP26. The final declaration gives prominence to cities and regions, recognising them as important stakeholders in addressing loss and damage, building resilience on the ground and contributing towards achieving the Paris Agreement goals.

“From a broader perspective I think the climate consciousness is clearly getting stronger, and it now goes beyond just a small civil society movement,” said Jean Baptiste Buffet, Senior Advocacy Officer with the United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), the world’s largest organisation of local and regional governments. “Leaders and private corporations are certainly feeling this pressure.”

Globally, COP26 has delivered many positive outcomes, including ending deforestation, drastically cutting methane emissions, and increasing ambitions in some countries, “but actions will need to follow and it remains unclear how we can monitor these announcements,” Buffet noted.

From this perspective, the Scottish COP hasn’t been much different from its previous iterations. Representatives of local and regional entities present in Glasgow felt that urban and regional voices have not been adequately integrated in the national framework of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Without vertical integration, said Buffet, “we will miss the Paris Agreement’s targets: multilevel action is needed today more than ever as the climate emergency is also about preserving the local delivery of public services for our communities.”

COP26: Cities Become More Important in the Climate Change Conversation

Speaking in front of the organisation’s online plenary, Emilia Saiz Carrancedo, UCLG’s secretary general, noted that climate is a compounding threat that adds to the social and economic challenges cities are already facing; “migration, health, systemic inequalities – they all affect our cities today,” she said.

Despite still being sidelined at the negotiating table, the importance of cities in the climate change conversation is only growing. Urban centres are estimated to be responsible for around 75 per cent of global CO2 emissions, mostly due to cars and other forms of transport, as well as the construction industry. In the developing world in particular the problem is set to become even more acute, as more people migrate from rural areas made increasingly inhospitable by climate change in search of a better life in the city.

Vulnerable Coastal Cities: The Case of Mumbai

India, one of the world’s most populous countries as well as one of the most vulnerable to climate change, is an example of this trend: according to the International Energy Agency (IEA) the country is expected to add the equivalent of 13 Mumbais to its population within 20 years, most of whom will reside in cities, doubling the number of existing residential buildings.

Mumbai, the capital city of the state of Maharashtra, exposed to coastal erosion due to sea level rise and unfettered industrialisation of its shores, embodies India’s population boom as well as the vulnerabilities that coastal megacities face all over the world. In the case of Mumbai however, meteorologists warn that a warmer ocean will send more frequent and erratic storms crashing on homes and infrastructure built too close to the sea. This year, the government of Maharashtra joined the UN Race to Resilience campaign, the first programme to bring all levels of local governments and stakeholders to the forefront of mitigation and adaptation in some of the world’s most vulnerable areas.

“In Cities, We Are The Doers”

While the magnitude of this transformation brings unprecedented risks, these can only be tackled from the ground, not just in the Global South but in every city facing the growing impacts of climate change – be it heatwaves, floods, or water scarcity – and cities have a solid track record when it comes to action. The mayor of London Sadiq Khan, who chairs the mayor’s network C40, reminded the summit that two thirds of the 97 C40 member cities have met and exceeded their share of the Paris Agreement targets. Following the announcement that the network had mobilised $1 billion of investment to deploy clean public transport across Latin America, Khan chastised country leaders: “In cities, we are the doers, in contrast to national governments who are the delayers, kicking the can down the road to 2040 or 2050.”

Local leaders agree that some positives have been achieved at COP26, including a new UK-backed Urban Climate Action Programme (UCAP), for which the COP host pledged £27 million to support cities across Africa, Asia, and Latin America to reach net zero emissions. However, on broader, systemic issues that cities and regions representatives were hoping would be addressed, the talks have fallen short. Questions on how to secure adequate financing for cities in the developing world, as well as ensuring better representation of regions and cities within the negotiations, will remain open for another year. But the work between now and COP27 in Egypt doesn’t stop: “We may not be able to impact the negotiations,” Saiz Carrancedo said, “but we are certainly going to be able to impact the future policies and the implementation of the commitments.”

- COP27: Equipping Today’s Cities for Tomorrow’s Climate Crises - 21. November 2022

- At COP26, Cities were Climate Action Watchdogs - 23. November 2021

- COP24: What Does it Mean for Cities and Regions? - 17. December 2018