An Epidemic Might Cure Venice

Researchers from MIT Civic Data Design Lab investigate Venice’s tourism dynamics by employing spatial data on urban form and tourist facilities. Their goal is to envision what Venice’s post-pandemic urban life could look like.

When the virus locked Venetians inside their homes and tourists outside Italy, the lagoon city could finally breathe. Residents felt the emptiness from their balconies and streets as the coronavirus crisis calmed the city and left it without visitors for the first time in living memory: before the pandemic cancelled flights, some estimate that 30 million tourists visited Venice each year.

With the city’s tourism industry forced to a halt, local officials now have a chance to reimagine a balanced economy that accommodates tourists while maintaining permanent residents’ quality of life – a balance that overtourism fails to achieve. The spatial dynamics of overtourism are complex and little examined. In order to face the challenges of omnipresent tourism, we must understand how the symptoms of overtourism present themselves on the ground.

Building a Granular “Tourism Index”

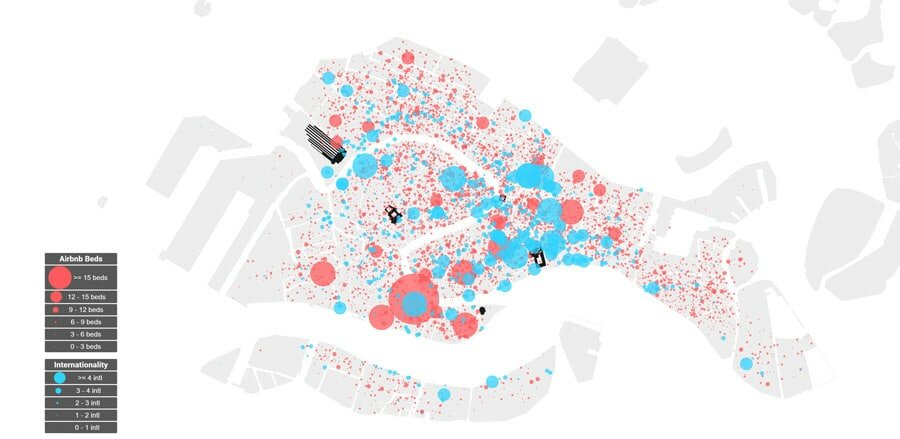

Our interdisciplinary team from MIT Civic Data Design Lab built a “Tourism Index” which identifies hotspots of high-intensity tourism in order to provide spatial information for data-informed policy. We compiled data about 6642 Airbnb rentals, tourist-oriented shops (such as souvenirs stores, mask shops), and the languages and nationalities of TripAdvisor reviewers in 997 Venetian restaurants – all of which are considered direct and indirect symptoms of overtourism.

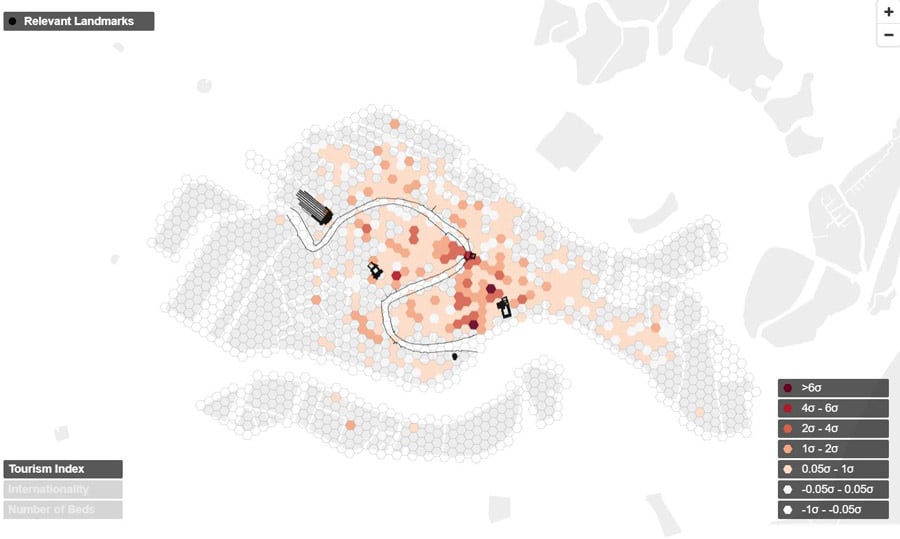

We are aware, however, that this task is complicated since the boundaries between industries serving tourists and those providing services to residents and commuters are ambiguous. We visualised these variables in the historic centre of Venice and constructed a “tourism score” at a granular level. With a systemic yet site-specific understanding of overtourism, we demonstrated how tourism is not ubiquitously affecting the historic centre of Venice.

Airbnbs and internationally attended restaurants in Venice; Source: http://www.overtourismvenice.mit.edu/ | © MIT, DUSP

The “Tourism Index” illustrates shopping, dining, and short-term rentals spatial patterns. At the centre of the city, for example, the San Polo and San Marco neighbourhoods boast some of the highest tourism scores in the areas adjacent to the Rialto Bridge and St. Mark’s Basilica. We also detected a line of expensive designer shops running straight from Rialto Bridge to Piazza San Marco, the path many tourists take to hit the most iconic landmarks. Restaurant “Internationality” scores, indicating reviewers from outside of Italy and foreign-language speakers, were also high in this region.

As Airbnb properties remain mostly empty in the midst of this pandemic, the municipality is already thinking of a plan to temporarily convert Airbnb units into student housing for the island’s two universities. However, a public call for a flexible use of the privately-owned housing stock seems quite hard to be operationalised.

“Tourism Index” map | Source: http://www.overtourismvenice.mit.edu/ | © MIT, DUSP

How does Urban Form Relate to Tourism?

Encouraged by this initial mapping effort, our team investigated the urban form of Venice – from the distribution of landmarks and their popularity (according to Google Places reviews) to average street width changes at intersections. We used a spatial regression model to predict “Tourism Index” scores and identify urban form types prone to becoming tourism hot spots while controlling for neighbourhoods and percentage of built land versus water.

A group of tourists snaps some selfies from the ground floor of the former Palazzo Reale, at the west end of Piazza San Marco, looking out from the deep shade of the classical arcade. The numerous arches of the Procuratie act as urban frames for astonishing views of San Marco Basilica | © Jiakun He, 2018

Popular landmarks and changes in street-width (like the leap from narrow alley to wide piazza) predicted high tourism levels across the city. American urban planner Kevin Lynch described space in the city in his 1952-1953 travel diary as, “constantly changing narrow slits to broad openings, dark to light.” These spots, where pedestrians tend to slow down to reorient themselves because of the sudden change in their physical surroundings could be labelled by the city as prone to touristification.

Landmarks’ popularity (red) and percentage of open spaces in each hexagonal cell (green) | Source: http://www.overtourismvenice.mit.edu/ | © MIT, DUSP

How Can these Insights Positively Influence Decision-Making?

As a next step, these high-traffic corners could be bookmarked for businesses that promote local culture and learning. Mayor Luigi Brugnaro suggested that the city start a climate change research centre to attract scientists, and local civic groups want to incentivise artisans to return to the historic island. New academic and artistic centres could be intentionally housed where hollow, consumer-based tourism used to prevail. Nowadays, most Venetian workers are dependent on tourism for jobs, so a post-pandemic Venice will need to facilitate job training and opportunities in these diverse sectors.

A lost tourist stands at the intersection of two narrow calli (Venetian streets). | © Jiakun He, 2018

With this granular information about the relationship between urban form and tourism, policymakers can make context-specific decisions. For example, regulating the number of tourist shops in an entire neighbourhood amounts to an arbitrary administrative boundary that lacks information about the inherent complexity of urban spaces and how people behave in them. Instead, as our study suggests, cities should systemically look at the micro-scale by questioning how landmarks and urban form influence the distribution of tourism activities.

Planners can replicate this data-driven approach in other tourism-dependent cities to understand the spatiality of tourism dynamics. Concerned citizens can better advocate for resources necessary for urban life like convenience stores and supermarkets with specific information about current businesses.

With international travels grinding to a halt due to the pandemic, there is an unprecedented opportunity to address overtourism. If the 1631 epidemic gave Venice one of the most iconic landmarks ¬– Santa Maria della Salute –, businesses for locals can monumentalise a post-pandemic balanced urban life. Turnstiles at Piazza San Marco will be relics of the past, no longer needed to quell the crowds.

Santa Maria della Salute was built to celebrate the end of the 1631 epidemic | © Jiakun He, 2018