Encouraging Greater Walking and Cycling in Tshwane

Tshwane, South Africa, wants to encourage walking and cycling among its residents. Michael Kihato from C40 Cities Finance Facility outlines challenges and solutions in one of the country’s three capitals.

Walking and Cycling in Tshwane – Facts and Figures

Walking and cycling is a vital mode of transport in Tshwane, South Africa, constituting almost a third of all trips in the city, with 29 and 2 per cent of trips, respectively. These are municipal averages, and the numbers are much higher in lower-income areas, peaking at over 60 per cent in some suburbs. After the ubiquitous minibus taxis, walking and cycling are the most important modes of transport.

The national policy target is that households should spend 10 per cent or less on transport costs. Yet, even with the current high rates of walking and cycling, this target has not been achieved. According to the city’s travel surveys in three of the lower income areas in the city, for example, households often spend 15, some even more than 30 per cent on transport.

This implies two things: first, not enough mobility happens through walking and cycling. And second, it is very likely that walking and cycling are combined with more costly modes of transport, during a single trip. This is due to the spatial nature of Tshwane, where distances to work and other daily destinations do not permit the sole use of walking and cycling.

The city has set ambitious targets: 50 per cent of trips under two kilometres to be done walking, and 10 per cent of longer trips by bicycle, effectively doubling the current numbers. To reach this goal, the city needs to address several challenges: changing the spatial configuration of the city, and promoting a cultural shift towards walking and cycling.

The Spatial Challenge

South African cities, and Tshwane is no exception, tend to sprawl. This is a remarkably persistent legacy of Apartheid. Urban spaces are characterised by mono-uses with separated residential and work areas, and long daily commutes between the two. The average trip in the city is 30 kilometres, and trips as long as 50 kilometres are not uncommon. In fact, the trip Tshwane CBD to the former homeland of Kwa Ndebele is the longest daily subsidised commuter bus trip in the country at over 100 kilometres.

More than half the work trips in the city take more than 45 minutes, and in lower income suburbs such as Soshanguve, Mamelodi, Ekangala, and Wallmansthaal they often take an hour or more. Such distances make walking and cycling as modes of transport impractical. Thus, they are counteracting efforts to reduce emissions and create financially sustainable delivery of public transport.

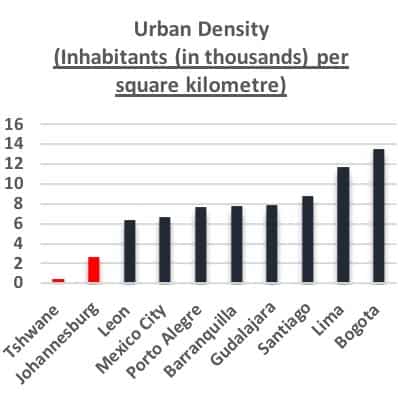

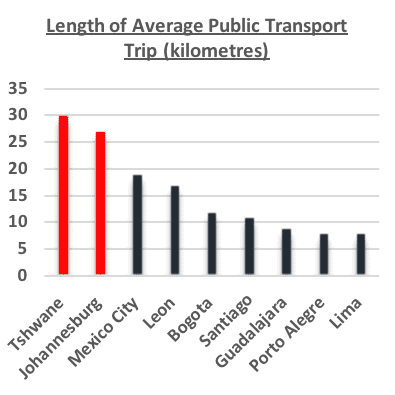

An international comparison between some Latin American and South African cities illustrates that Tshwane ranks lowest in urban density while highest in length of public transport.

Figure 1: Urban Density. Numbers derived from: City of Tshwane (2013) and Scorcia, H & Munoz-Raskin, R. (2019)

Figure 2: Length of Average Public Transport Trip. Numbers derived from: City of Tshwane (2013) and Scorcia, H & Munoz-Raskin, R. (2019)

The Cultural Challenge

A second challenge the city needs to confront is the “social stigma” associated with walking and cycling. The city acknowledges that these are not modes of choice for most users. Indeed, it is largely seen as used by a captive market in a society where car use is aspirational, associated with success and achievement.

Confronting These Challenges

Tshwane has developed elaborate transport and spatial policies and plans. Regarding the spatial challenge, one strategy is “spatial targeting”: using its financial and regulatory tools, the city targets delivery of mixed-use, high density, inclusive work, and residential developments within selected geographical areas. Many of them are located within lower income and spatially excluded suburbs where walking and cycling can become more feasible and grow through targeting.

The city also incentivises a cultural shift towards walking and cycling. It has promoted large-scale cycling events including open streets, car free, and cycle to work festivals. It promotes partnerships with businesses to commit to more walking and cycling culture among staff. The city is also part of a pilot project for e-bikes and has provided access to bicycles in lower-income areas.

There are no quick fixes to the spatial challenge, and the current focus on spatial targeting is one of several strategies. However, it is important to ensure that the developments created by this strategy are inclusive, and do not result in gentrified suburbs that fail to incorporate lower income households. The city also needs buy-in from other important players to increase investment in these targeted areas.

These include other governmental organs, particularly the state rail provider, national departments owning land, and deliverers of walking and cycling infrastructure such as the provincial department of transport. The private sector needs to see value in investing in these areas. This coordinating and influencing role of the city is immensely important.

The cultural shift is no less complex to resolve. Much of the current values are rooted in a historical bias in favour of car ownership and are supported by regulatory, policy, and fiscal systems, resulting in car-centric spatial planning frameworks. The car industry plays an important and iconic role in the South African economy.

While there has been encouraging increase of allocations for urban public transport in recent years, these have not always yielded the desired outcomes and are still dwarfed by road-building priorities. Rail service has declined in particular, despite it being a key mode of connecting walkers and cyclists in low income areas to jobs in Tshwane CBD and other parts of the province. Some of these issues can be addressed on city level through local spatial regulations or greater allocation of locally collected taxes. However, to succeed, we need a bigger change to the national fiscal and policy infrastructure. This needs to be done and championed by the city together with other metropolitan cities going forward.

- Encouraging Greater Walking and Cycling in Tshwane - 26. May 2020