Celebrating Human Diversity – Urban Planning for Disability Equity and Inclusion

The ways we plan and design for human diversity require serious rethinking if we genuinely want to address inequity and injustices in our suburbs and cities. By Lisa Stafford

Disabled people have been forced to live with social and spatial exclusion and immobility due to exclusionary planning and design decisions. These decisions about spatial design and functionality of environments are often based upon a narrow body type that can be described as “young adult fit white male” and “average person.” Favouring these body types is a form of Ableism – a prejudice that subjugates all other bodies and produces exclusion.

For the 1.3 billion disabled people globally, developing robust planning approaches for inclusion and equity reflecting body-mind diversity across ages, gender, and cultures are critically needed.

Being excluded spatially impacts everything that many take for granted – from going for walks, using public transport, where you can work and study, seeing friends, attending appointments, going out, recreation and leisure as well as secure accessible housing, to name a few.

What Changes Are Needed?

To right these wrongs, a range of changes are needed in how we plan, design, adapt, and retrofit our suburbs and cities for sustainable inclusive futures. These changes seek to ensure that disabled people’s rights to everyday spaces, housing, transport, and other social infrastructure and services are actualised as per the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Planning Inclusive Communities project in Australia worked with 97 affected citizens with and without disability and chronic illness 9-92 years of age to identify the changes needed in the ways we plan for equity and inclusion based on current realities and experiences of living in the suburbs, cities, and regions. These included: commitment to disability justice, changing the narrative about disability and confronting ableism, as well as adopting inclusive urban governance, planning and design practices, education, and leadership.

Commitment to Disability Justice in Urban Planning

If we are serious about equity and inclusion as a key focus of the New Urban Agenda and SDG 11, then we need to think about disability justice (DJ).

Disability Justice by Sins Invalid is an evolving framework underpinned by ten core principles: Intersectionality, Leadership of Those Most Impacted, Anti-Capitalism, Cross-Movement Solidarity, Wholeness, Sustainability, Cross-Disability Solidarity, Interdependence, Collective Access, and Collective Liberation. Demanding and valuing difference, self-determination, and equity are central to the DJ framework and its interconnections with other injustices like climate and racial justice. The use of body-mind is also prevalent within DJ to contest normative ideas of body and mind as separate entities, to reinforce the complex interconnectedness between our mental and physical systems, while also recognising intersectional power dynamics in everyday life influencing different body-mind experiences.

What makes community inclusive? © Lisa Stafford

Urban planners need to understand and plan for disability justice because their roles are integral components in unlocking these injustices spatially. A simple way of incorporating DJ thinking in practice is giving deliberate attention to and making a concerted effort to understand the diverse ways body-minds inhabit, sense and experience space, the intersecting oppressions faced in everyday life by various disabled people and communities, and the role planning and design plays in influencing these experiences. This understanding must be generated from listening and being led by lived knowledge of diverse affected citizens and communities.

Changing the Narrative about Disability and Confronting Ableism

Ableism prevents celebrating and planning for human diversity. Planning for the “average person”; the relegation of planning for “disability access” to comply with minimum design standards; and viewing disabled people as a minority to justify a shortage of investment are examples of acts in planning that continue exclusion and constrain possibilities for inclusive communities, cities, and regions.

Society must ensure that disability is accepted as a natural part of being human. Within the course of life, everyone will have an experience of disability – whether that is you or your loved ones, and whether it is permanent, temporary, or episodic.

To make this change, we need to affirm our diversity in body-minds across ages, genders, and cultures; recognise ableism and how it operates in planning; and reinforce that planning for the average is an exclusionary practice.

Adopting Inclusive Urban Governance, Planning and Design Practices, and Education and Leadership

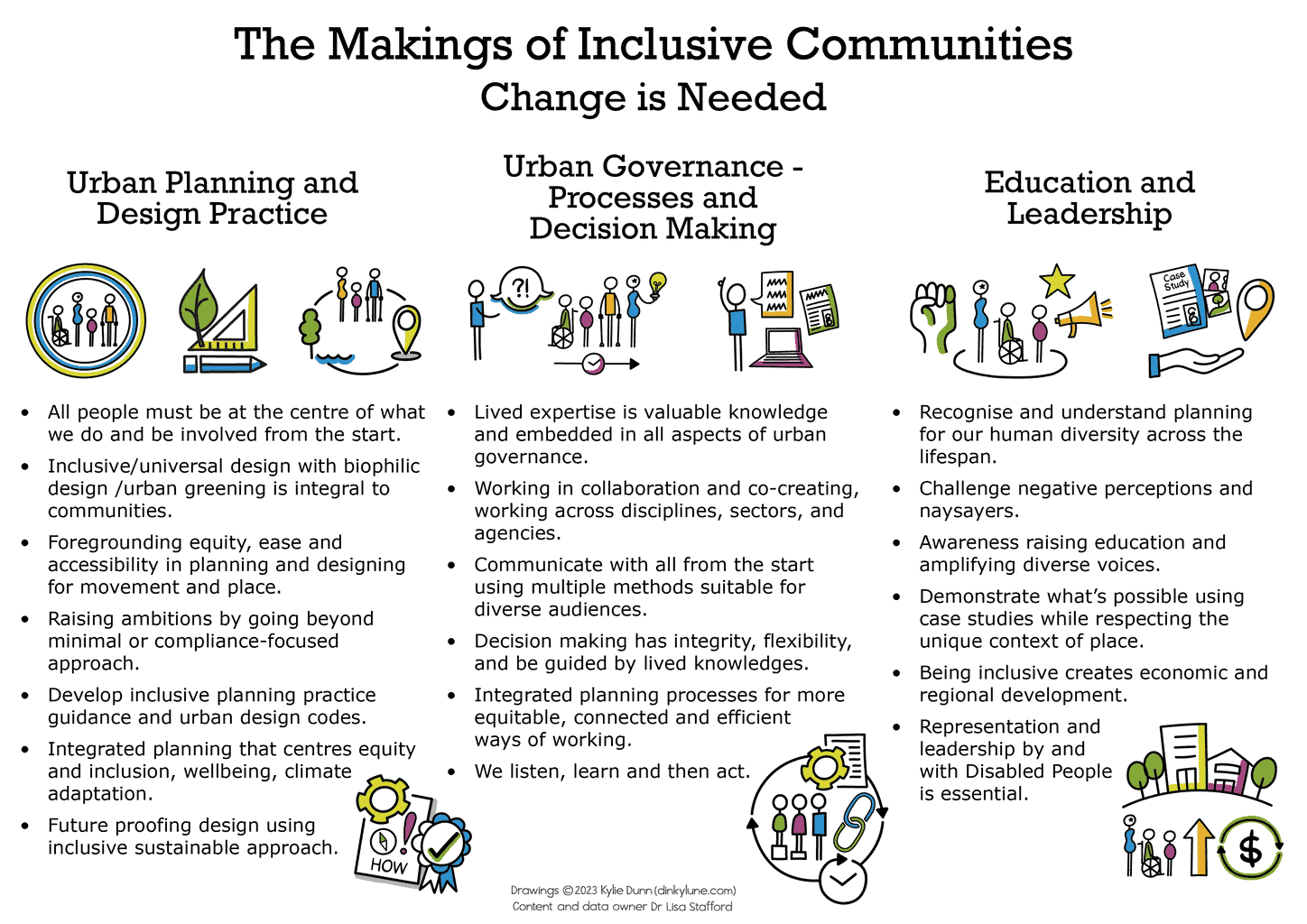

To plan inclusive communities and cities, significant change in our approach is required to address the key drivers of exclusion and inequity experienced by disabled people. Our research identified an emergent framework of change needed across three key areas of urban planning: Inclusive Urban Planning and Design Practice, Inclusive Urban Governance, and Education and Leadership. A developed framework (Figure 1) provides a beneficial tool for planners, designers, policymakers, and urban leaders to work towards achieving more inclusive sustainable suburbs and cities. These are not fixed or exhaustive, but reflective of what participants commonly conveyed as being central in shaping inclusive communities and cities.

Change Needed in Making Communities Inclusive © 2023 Kylie Dunn (Dinkylune)

There was a strong sense among participants that change must come from a place where disabled people are viewed as equal. Moreover, inclusive suburbs and cities should be valued as core assets, which are embedded in planning systems, policies, education, practices, and processes with enduring investment in inclusive suburbs and cities.

Planning for equity and inclusion is an essential approach. We simply will not have sustainable suburbs and cities if they are not inclusive and just. The message for our profession is simple – we must do better. Be a change agent by considering your ways of working and what it means to plan better for equity and inclusion.

- Celebrating Human Diversity – Urban Planning for Disability Equity and Inclusion - 19. September 2023