Adopted Spaces: How Social Life on India’s Streets is Increasingly Threatened by Top-down City Planning

By Sneha Mandhan

In India’s bustling cities, time spent in public spaces is an integral component of everyday life. Street design that focuses on motorised traffic does not take into account this human quality of street life. Instead, local practices and human activity should inform city planning, argues Sneha Mandhan.

Haggling with vendors, eating at a high table on the street outside a Darshini (local restaurant that offers only local delicacies), getting the tyre of your car replaced, and sipping a cup of chai at a paan stall (sweet made with betel leaf) forms the hustle and bustle that defines the experience along Gandhi Bazar in the Basavangudi neighbourhood of Bangalore. This reflects the local street culture of most Indian cities, where the street forms the stage on which the choreographies of mundane daily activities form a comfortable rhythm that manifests the collective identity of the city’s public. However, this local street culture is increasingly threatened by the influence of globalisation. Wide, sweeping roads with speeding cars are replacing the humanly scaled, bustling streets that are emblematic of local Indian culture.

The physical combines with the active to offer multi-sensory stimulation along the street. Gandhi Bazar, Basavangudi, Bangalore – Photo: Sneha Mandhan

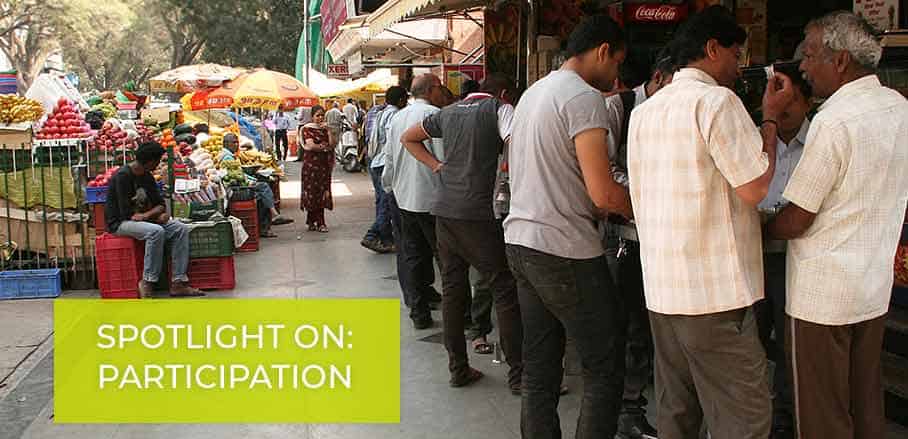

Sidewalks offer a respite, a pause, and a common ground for people of various castes, religions, and genders, to interact and coexist. Gandhi Bazar, Basavangudi, Bangalore – Photo: Sneha Mandhan

One of the last remaining public spaces in the city

In the introduction to the August 2012 issue of Seminar India, Curt Gambetta and Ritajyoti Bandhyopadhyay ask, “What is the future of the street?” They characterise the problem facing Indian streetscapes as one of “impending obsolescence, as though the importance of the street as a conduit of social life may well be a thing of the past” (Gambetta and Bandyopadhyay, 2012). However, this is far from the truth. As Indian towns and cities grow and become increasingly privatised, streets remain some of the last democratic and inclusive spaces where urban residents can interact, congregate, and celebrate.

Streets in India have traditionally been the intermediate spaces that negotiate between the private and the public. Women would customarily spend the day gossiping, sorting pulses, cutting and pickling vegetables, and washing clothes on the sidewalks fronting their houses, while enjoying the sunlight and conversing with neighbours and street vendors passing by. Today with changing urban lifestyles, the preference for vehicular traffic, and the strong influences of ‘global’ urban planning principles on local street design guidelines, many of the activities generated by street frontage are at risk.

Women actively co-opt sidewalks through the spillage of activites from the semi-private onto the public. Hebbal, Bangalore – Photo: Sneha Mandhan

As Indian cities densify, streets remain some of the last truly open, public spaces that offer respite to urban dwellers. In the words of sociologist Arjun Appadurai, “Streets, and their culture, lie at the heart of public life in contemporary India. Especially in those many cities where urban housing is crowded and uncomfortable, and where the weather is never too cold, streets are where much of life is lived” (Appadurai, 1987). Streets are adopted by the public; they are ‘cohabited spaces,’ ‘life worlds,’ and ‘a theatre of contiguity, change, conflict and conviviality’ (Mani, 2013). They serve not only as corridors for circulation and open spaces for recreation, but also as canvases for public expression against political regimes, for social events, and for religious rites.

During religious processions, the streets which are normally the ‘neutral’ spaces within cities, become “marked by the claims of various communities and interest groups.” (Appadurai, 1987) J.C. Nagar, Bangalore – Photo: Sneha Mandhan

Who designs the streets?

In 1999, the chief minister of the state of Karnataka established the Bangalore Agenda Task Force, a public-private partnership headed by the former CEO of Infosys Technologies, Nandan Nilekani. The Task Force consisted of several nominated members, many of whom were from the corporate world, charged to design an agenda for development of the city including its infrastructure and urban service networks. Even though it was active only for five years, the Task Force demonstrated a trend that has become commonplace since India started implementing neoliberal policies in 1991. Private investors, who promote ‘modernisation’ and idealise ‘world class’ cities like Paris, London, and Tokyo, are now a significant voice in the planning of Indian cities.

Currently, most cities in India do not have street design guidelines to direct urban street planning. The guidelines that exist are primarily for national and state highways with minimal emphasis on urban roads and streets, and almost no consideration of pedestrian activity or accommodation for tyre repair shops or chai stalls. Street design is only beginning to be addressed by a few cities like Delhi, Ahmedabad, and Bangalore. But even these cities’ guidelines, while emphasising the primacy of streets as public spaces, mimic ‘global’ engineering standards at the expense of the vernacular design features of streets that make them conducive to public life.

Local chai and paan stalls punctuate the street with opportunities to take a break from a long day at work. Malleshwaram, Bangalore – Photo: Sneha Mandhan

Most regulatory literature, for example, consistently uses the term ‘road’ to refer to all types of urban streets. The Tender SURE (Specifications for Urban Roads Execution) Design Standards for Bangalore establish design guidelines, including widths for sidewalks and rights-of-way, based on hierarchies that are defined by “means of efficient access to dwellings and destination points within neighbourhoods; and as a means of mobility for all modal types and users” (Jana Urban Space Foundation, 2011). These hierarchies of arterial, sub-arterial, collector, local, and sub-local roads defined in the guidelines have origins in traffic engineering where access and mobility for motorized traffic, not for pedestrians or cyclists govern the design of street sections.

Large expanses of asphalted carriageways result in vehicular-centric roads that are not conducive to pedestrian activity. Whitefield, Bangalore – Photo: Sneha Mandhan

Local colloquialisms, however, embody different interpretations of the relationships between urban residents and their streets. In Bangalore, the Kannada term oni refers to a gully or an alleyway that is a part of one’s private space and is often the minimum setback between two properties. Beedhi refers to the frontage of the house on the street or the extension of the private quarters of the house onto the street. Terms such as raste (road), daari (way or path), and heddogai (big road or highway) distinctly refer to paths that are public and away from the home. These nuances and their importance for the function of streets in residents’ daily lives are often ignored. The result is the construction of streets that are vehicular-centric with wide carriageways, lacking in human scale, lined with high, blank boundary walls, and unwelcoming to pedestrians.

What is the future of the Indian street?

As the urban landscape in India is shaped by globalisation, it is imperative that we design for the local cultural idiosyncracies – for the local Darshinis and paan stalls – of Indian cities that are emblematised by the social life played out in their public spaces. Along Gandhi Bazar, high top tables on sidewalks where Kannadigas enjoy local delicacies neighbour high-end coffee shops where younger Bangaloreans lounge on couches and sip on frappes. Indian cities enable these juxtapositions of diverse and ever-evolving cultures and traditions, and it is important that the physical environment of the city continues to enable that.

Urban planning in India, like elsewhere, is mostly top-down. Public participation does not feature as an integral part of the planning and design processes in most public projects. However, urban perception and experience occur from the ground up. When designing urban streets, it is important that the regulatory literature identifies and emphasises the role of Indian streets as public spaces. Instead of drawing up generic guidelines for road hierarchies based on access and mobility, municipalities and other planning agencies must engage with urban residents to understand local relationships with streets. They must define new street hierarchies that respond to their cultural practices and engagements with these spaces, and focus on the pedestrian as a central actor in the design process. For example, in Bangalore, design guidelines for local and sub-local roads should be extended to include more complex and finer-grained accommodations for onis, beedhis, and daaris, where the local resident-street relationship drives design.

Visual cues direct pedestrians and create a sense of place. Chickpete, Bangalore – Photo: Sneha Mandhan

For Indian cities to continue to thrive as vibrant, inclusive centres of social and economic activity, the voice of the local population must become a vital part of the design and planning processes to ensure that designs are reflective of urban culture, grounded in the vernacular, and owned by the public.

References:

Appadurai, A., 1987. Street Culture. India Mag. 81 12–22.

Gambetta, C., Bandyopadhyay, R., 2012. Streetscapes – The problem. Seminar India 636.

Jana Urban Space Foundation, 2011. Tender SURE Volume 1: Design Standards.

Mani, L., 2013. Integral nature of things: critical reflections on the present. Routledge, London; New York.