Storm-Proof Housing for the Urban Poor – Lessons from Da Nang, Vietnam

For low-income families in coastal areas of Vietnam, storm and typhoon damage is a constant threat to life and well-being. However, there is a way for them to escape the vicious cycle, involving proper financial and technical support for storm-resilience housing. Nguyen Anh Tho presents experiences from Da Nang City.

Damages in Da Nang following Typhoon Nari © Phong Tran, ISET-Internationals 2013

Why are Poor Communities Most Vulnerable to Natural Hazards?

Early in the morning of October 15, 2013, Typhoon Nari made a landfall on Da Nang on the central coast of Vietnam. For eight long hours, constant violent winds, peaked at Category 1, up to 130 kilometres per hour, battered the city, and the accompanied heavy rainfall caused flooding in many areas. Da Nang was not the city experiencing the worst impact of this monstrous storm, yet twelve people were injured, 122 houses were destroyed, 178 houses partially collapsed, and thousands of roofs were ripped off. Key urban services such as power and water supply, transport, lighting and communications were also heavily disrupted in several areas of the city.

For any family in Vietnam, housing is typically the single most valuable asset. A Vietnamese saying goes ‘Safe housing, sound livelihoods’ (an cư, lạc nghiệp), which represents a strong belief that good housing is the foundation of a good and stable life. However, it is a sad reality that most poor and near-poor households live in fragile housing units, often in areas prone to the impacts of natural hazards such as storm, flooding, erosion and landslide, and thus are highly susceptible to the destruction or damage by these hazards.

An event like Nari is not an exceptional situation for Da Nang. The last equivalent storm was Typhoon Xangsane in 2006, the next in the line was Category 2-3 Typhoon Molave in 2020, and that is not including a number of times when the city narrowly escaped direct encounter with other violent storms, including Typhoon Haiyan earlier that November 2013.

The future is even bleaker with projections of increased storm intensity under the effect of global climate change. Moreover, Da Nang, as with any other province or city in Vietnam nowadays, is undergoing a rapid urbanisation process, which often robs away natural areas such as coastal mangrove forests or water surfaces that act as the natural buffer and shield for houses from the devastating impacts of floods and storms. And poor families’ housing is caught in an even direr situation.

This results in a vicious cycle of poverty, fragile housing, storm destruction, poverty, fragile housing, and another storm. Families may be lucky enough to receive support from housing programmes for rebuilding after a storm, but most of the time the financial support is inadequate and the house design and construction are not robust enough, so the risk of damage or destruction in the next storm around is still very high. Their financial situation does not allow for proper reconstruction, or for access of a formal loan to this purpose, thus they have to keep living in this vicious cycle and accept that there are always some months during the storm season when they almost never feel safe or sound in their own home.

How Can Poor Households Become More Resilient to Storms?

The housing damages by Typhoon Nari, as accounted above, were devastating to poor people’ houses, especially in shorefront areas of Da Nang. Yet in eight wards/communes right next to the sea (in Hoa Vang, Son Tra, Ngu Hanh Son and Lien Chieu districts), there are small pockets of houses that, despite belonging to poor and near-poor households, still stood firm and suffered no damage from the fierce storm. They are the 244 beneficiary households under a resilient housing credit programme implemented by the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-International (ISET) in collaboration with the Women’s Union of Da Nang City. According to ISET’s investigation, in the very same wards and communes where these 244 houses are located, 68 totally collapsed, 88 partially collapsed, 540 roofs were totally torn off, and 2,270 roofs were partially torn off, making a total of 2,996 damaged houses.

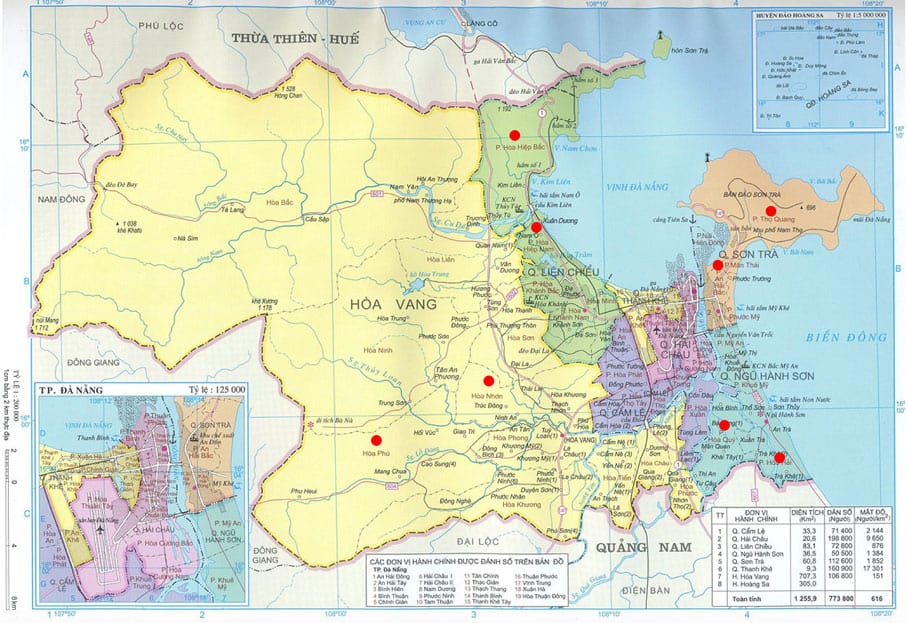

Locations of 8 beneficiary wards under ISET’s housing project in Da Nang as of 2013. In subsequent years, the project was rolled out to reach more household and additional wards in Da Nang, as well as other provinces in Vietnam. But Typhoon Nari was the first critical test to the project model. It later received UNFCCC’s Lighthouse Award in 2014 © Center of Survey and Mapping Data, modified by the author.

There are two key elements to the support to these 244 households under this project:

(1) A credit loan for house retrofitting or rebuilding, with loan amount and payment schedule tailored to the needs and income stream of specific households, given the household’s commitment to following recommended storm-resilience guidance; and

(2) A storm-resilience technical design for the retrofitting or reconstruction.

The credit loans, granted at a low interest and with a prolonged payment schedule, were managed by the Da Nang Women’s Union, who with a network extended to the grassroots level, stayed attune to the personal and financial situation of each household to make sure repayments are made on time, and that if the household face any unexpected difficulties, to reasonably delay their payment schedule as needed.

The technical design of each house reinforcement or construction work is provided by Central Vietnam Architecture Consultancy (CVAC), a local architecture company, who closely investigated each household’s needs to draw the design, and provided regular monitoring during the construction process to make sure all required storm-resilience techniques and features are included. The five-fold storm-resilience features include: (1) Simple building forms; (2) Appropriate pitch roofs from 30-45 degrees; (3) Stronger housing structure; (4) Safe failure by using a solid room in the house; and (5) Secure connection between roof elements and main structure.

For more detailed instructions for storm-resilience of low-income housing, please take a look at the following publications and project details: Support to Community-Based Disaster Risk Management in Southeast Asia, Technical Handbook on Design, Construction and Renovation of Typhoon-Resilient Low-Income Housing, and A Concept of Resilient Housing: Da Nang, Vietnam.

Leader of Saving group, Da Nang Women’s Union and household member inside her Storm-resistant house © Tho Nguyen, ISET- International, 2012

What Lessons Can Be Learned from the Da Nang Project?

This project provides a good lesson for every disaster prevention and reconstruction effort, not only in Vietnam, but every corner of the world where the rural and urban poor are still facing house damage or destruction by natural and manmade hazards. The first lesson is that the provision of loan should be accompanied with adequate assistance in the management of families’ income and repayment of the loan. A small grant alongside the loan will provide an extra boost for very poor households. If a loan is given without the help in spending it wisely, or in managing repayment, it might end up not doing any good for the household, and even become an extra burden to them.

No less important, this project has proved that there exist feasible technical solutions for building storm-resistant houses at low cost. The key is to build people’s awareness about these solutions, and emphasise the need to strictly follow the technical instruction in the building process. Many households in the project built the house with their own labour, with support from family, friends and neighbours, showing that the construction techniques can easily be replicated.

Every credit and/or housing support programme must keep in mind these two principles to make sure the support is meaningful and actually brings about positive change to people’s lives. These are important lessons in the face of another bad storm season this autumn and winter when La Niña is expected to return with similar intensity as the 2020-2021 event.