Quality Urban Fabric Will Determine the Fate of Tomorrow’s Cities

While we assume cities will continue to face rapid growth, the COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced a trend which counters linear population projections: qualified professionals no longer move where work is, but work from where they want to live. If, before the pandemic, cities competed to attract head offices or multinational corporations, today they have to compete for each qualified individual.

Asian cities co-exist in two parallel realities: one impacted by post-industrialisation and the other influenced by digital transformation. On the one hand, the labour distribution in Asian countries is still dominated by agriculture, retail and wholesale services, manufacturing and transportation, and construction sectors, together accounting for 70 per cent of total labour which cannot be managed remotely.

On the other hand, qualified workforce is catching up on Western trends of evermore remote work cultures. A McKinsey assessment states that five times more employees work remotely and moved out of congested urban cores to smaller cities and towns for an improved quality of life during or after COVID-19. This holds particularly true for high-income Asian countries, but cities in low and middle-income Asian countries are gradually catching up. Nearly 2.6 billion out of 4.7 billion people use smartphones in the Asia-Pacific region and e-commerce platforms, now massively accessible, have greatly boosted livelihoods of local artisans and farmers.

What Is Driving Urbanisation of Post-COVID-19 Cities?

If jobs and services are gradually losing the driving seat of urbanisation, we need to understand what is taking over this seat instead. At UNICITI, we argue that it is the very elements we neglect in the race for rapid infrastructure development today: sustainability and quality of life. Sustainability because, when choosing a place to live, one wants to have, for example, a steady and a reliable water supply tomorrow, no threat of regular floods, or heavy urban heat island effect. Quality of life because, whenever given a choice, we want to thrive, not only survive.

The urban realm can offer unique features one can only find in a populated high-density settlement: creativity and personal development opportunities in contact with other people, diversity of environments and options all at close distance, stimulating social diversity. This, however, has to come on top of a healthy environment which positively impacts physical and mental health – not at its cost. A compromise on the latter is becoming less and less acceptable to those who can choose.

To Thrive Tomorrow, Cities Need to Make the Right Choices Today

The Global Infrastructure Basel Foundation assessed that 75 per cent of the infrastructure we’ll see in 2050 does not exist today. This means that if a city addresses today’s pressing needs of basic housing and infrastructure at the expense of climate resilience, sustainability, and wellbeing, it locks itself into decades of low-quality life patterns that will no longer be accepted tomorrow. In other words, every building, every road, every development project we approve today will have a positive or a negative consequence for its city for decades to come. A building is not a sculpture – we cannot remove it the next day we find out we don’t like it. If rapidly growing Asian cities want to thrive tomorrow, they must make the right choices today. And every choice counts.

In other words, the biggest challenge of Asian cities, and of cities in the Global South in general, is to reconcile the need for rapidly building affordable urban infrastructure to address tremendous infrastructure shortages today with the need for sustainable, liveable, and unique urban fabric to ensure the city is attractive and competitive tomorrow. Achieving this can only happen by bringing together approaches tailored to the local context and cutting-edge technologies.

We Need a Radical Shift at Building Level, City Level, and Policy Level

To support cities in this transition, UNICITI, which stands for uniqueness in cities, launched a non-for-profit initiative A Third Way of Building Asian Cities. Over 150 professionals across over 35 countries are helping us identify break-through solutions which can be deployed at scale in Asia. In this effort, we look at a radical shift at three scales: the building level, the city level, and the policy level. Here are a few examples of what can be done:

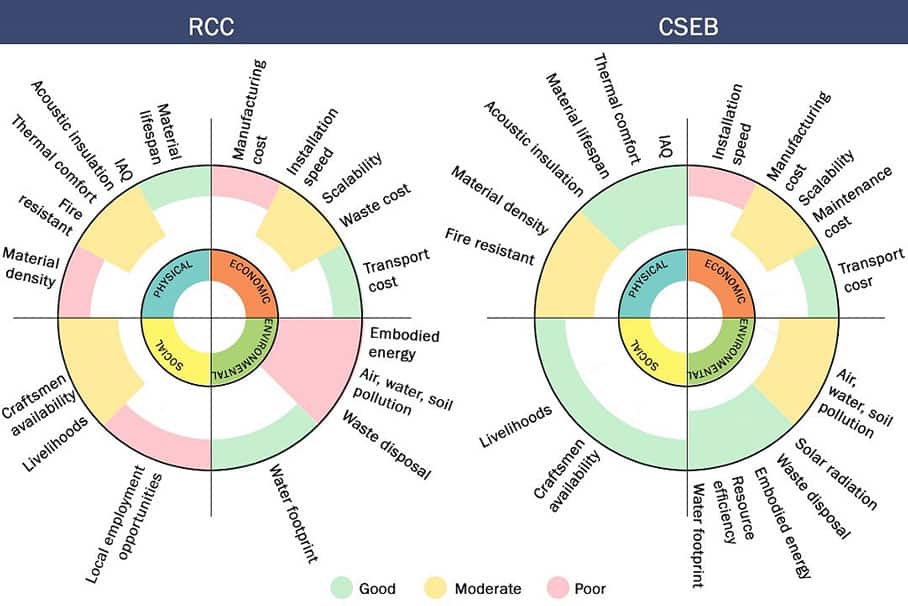

Building level: manufacturing of building materials alone accounts for 11 per cent of global CO2 emissions. Building operations lead to an additional 28 per cent, and accounts for 55 per cent of global electricity consumption. Today’s aspirational high-rise urban model limits the choice of building materials to the most carbon-intensive ones such as steel, aluminium, glass, or concrete. In cooperation with the Studio for Habitat Futures (ShiFt), we are hence putting in place a tool which holistically assesses building materials under environmental, physical, social, and economic factors.

For example, the tool shows that making walls with compressed stabilised earth blocks (CSEB) instead of concrete blocks in a building reduces its embodied energy by up to four times and substantially reduces air and water pollution because 95 per cent of the material is biodegradable. However, it also doubles the capital cost because skilled labour is scarce. The tool can hence inform policy makers: here for example, it demonstrates that upgrading the skills of local labour is key to mainstreaming the use of CSEB.

A comparative tool analysing sustainability of CSEB against RCC.

© A Third Way of Building Asian Cities, UNICITI

City level: urban population is increasing rapidly and so is the demand for housing: 600 million Asians still live in slums. This pressing demand leads to sporadic infrastructure development. Standardised new constructions, not tailored to local contexts, increase climate vulnerability risks and stand in isolation from the existing urban fabric, disrupting the visual identity of the city.

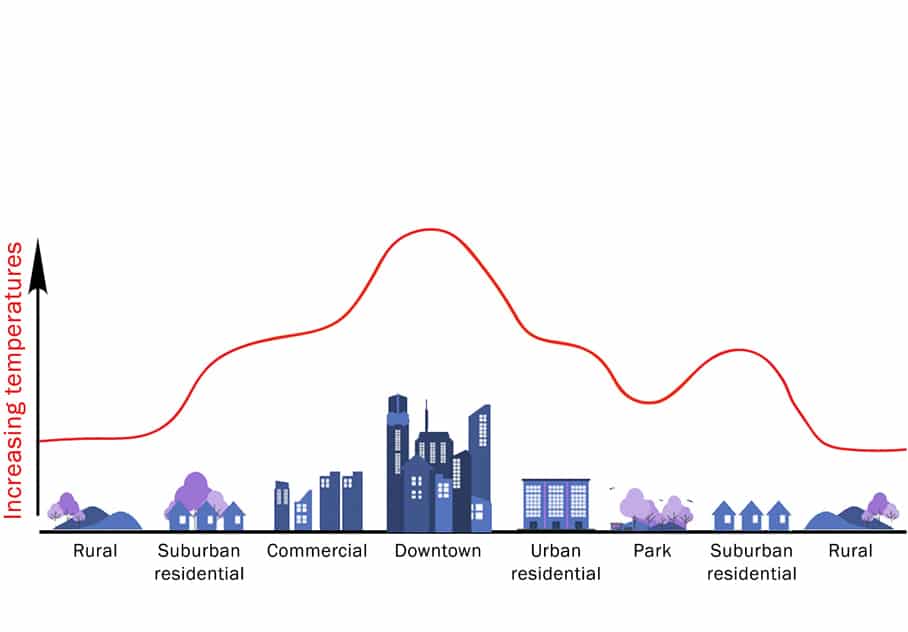

In cooperation with the University of Strathclyde, we tested a data-driven tool Urban Morphometrics. The tool generates building patterns which resonate with existing structures and helps promote organic, inclusive, and unique city growth patterns. Another example: an imbalance in the built-to-unbuilt ratio produces a sizeable urban heat island (UHI) effect. We are developing recommendations on a balanced distribution of built natural open spaces, compact neighbourhoods, and alternative materials for manmade open spaces to combat UHI.

Effects of urban heat island on different spaces.

© A Third Way of Building Asian Cities, UNICITI

Policy level: the breakthrough solutions identified in the first two scales require policy support, as well as economic and financial mechanisms. Policies include, for example, form-based codes tailored to the Asian context, or amending building codes to include sustainable building materials such as timber. Economic and financial mechanisms look at what makes sense to real estate developers today, while policies are not yet in place. For example, one of our teams is testing blockchain technology to estimate embodied energy of structures and developing incentives for the builders and developers to reduce embodied energy, in line with what has been done for operational energy.

We need to act fast before cities are locked into unsustainable and unliveable patterns for decades. If you think so too, whether you are a decision-maker, a research institute, a practitioner, or a passionate citizen, Asian cities need you.

To learn more and support our efforts, visit our website or our LinkedIn presence.