Perceptions Data Reveal Patterns of Tenure Insecurity in the Middle East and North Africa

Understanding what drives perceived security can help policymakers and urban planners make better choices. Shahd Mustafa shares new findings from Prindex’s report on land rights in the Arab region.

Last month, I spoke at the Second Arab Land Conference and was struck by the very different issues people from different countries wanted to talk about – everything from women’s rights and conflict to unaffordable rents and badly planned cities.

This variety is reflected in Prindex’s new report on land rights in the Arab region, which was launched at the conference and analyses citizens’ perceptions of tenure security. Our survey includes responses from over 13,000 men and women living in 13 different Arabic-speaking countries.

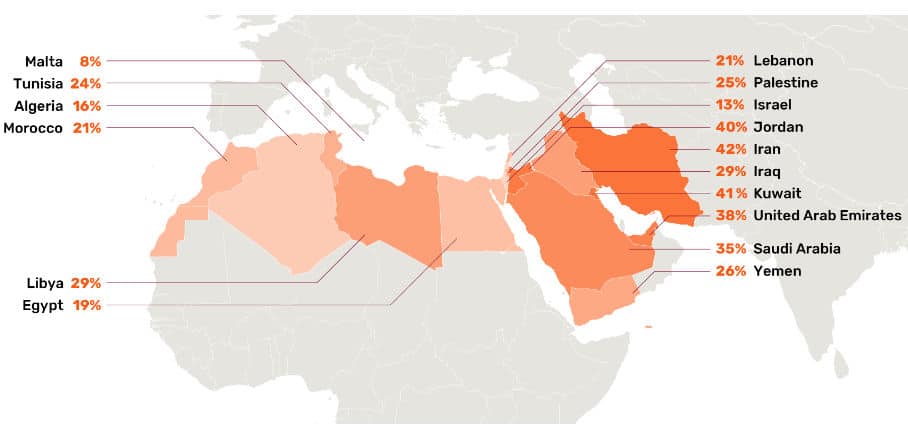

Beyond Arab countries, Prindex’s results for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) reveal a patchwork of perceptions. For example, people in Iran are more than five times as likely to feel insecure about their land and housing rights than people living in Malta.

Prindex results for the MENA region: average levels of tenure insecurity by country

The variety in perceptions makes sense, of course – the region is made up of many different cultures, landscapes, and economies, from tribal communities to megacities built on oil wealth, and everything in between. Yet, the report also finds some patterns of insecurity in the region. And, thanks to the fully comparative nature of the Prindex methodology, governments have the chance to use the data to see which policy solutions work best in similar settings.

Here are some of the key patterns that emerged from the data.

Conflict Drives Tenure Insecurity, but Refugee Host Countries are Worst Affected

Across MENA, Prindex’s representative study finds 28 per cent of people (78 million) feel insecure about their land and housing rights. This represents the highest rate of tenure insecurity for any region in the world, twice as high as North America (14 per cent), for example. Countries affected by ongoing conflict have relatively high rates of tenure insecurity, like Libya and Iraq (both 29 per cent), but it is countries that host refugees, like Jordan (40 per cent), which have notably higher rates.

Prindex data highlights the fragility of the situation for internally and externally displaced people, but also reflects the increased pressure on poor host communities. The influx of refugees into countries like Jordan, which has become a safe haven for people fleeing conflict in neighbouring Syria, Iraq and Palestine, has resulted in various informal settlements springing up on both public and private land around big cities. This can result in disputes between local landowners and displaced people, leaving newcomers highly vulnerable to eviction.

Cultural Practices can Override Legal Rights for Women

The region is undergoing rapid changes, yet there remains a high reliance on old customs and traditions. Inheritance laws in almost all MENA countries are inspired by Sharia law, which has provisions that enable women to inherit. The most common case is between siblings, where a sister should get half the amount of land or property her brother inherits (i.e. the son’s share is double that of the daughter’s from the same father). But in practice, daughters and sisters face enormous pressure to renounce their inheritance rights to male family members. They typically end up with nothing.

Today, especially in tribal and rural areas, land rights are often still decided through customary practices. These norms dictate that land stays in the name of the eldest male in order to keep land within the family. This is a vital issue for tribes in the region, which view power and authority as linked to the size of the land they control. The idea is to prevent women from transferring ownership through marriage to their husbands or children, thereby shrinking the family’s land.

Prindex data shows that women in the region are much more likely to fear eviction in the event of divorce or the death of a spouse than men. This gender gap is likely the result of cultural practices that deny women their legal right to inheritance. As women’s tenure security is often tied to them remaining in their marriage, widows face a precarious situation, and many other women may be trapped in unsafe marriages for fear of losing their home.

People in Richer Arab Countries are Even More Likely to Feel Insecure

Perhaps surprisingly, we found that rates of tenure insecurity are highest in stable, oil-rich Gulf countries like Kuwait (41 per cent), the United Arab Emirates (38 per cent), and Saudi Arabia (38 per cent). Such countries have experienced a construction boom over the last few decades, with luxury apartments and investment projects being developed to meet market demand. These properties are usually sold to foreigners or used as second homes, but are usually unaffordable for middle-class households and only serve to inflate land values and property markets. This leaves poorer people completely priced out in many urban areas in the region, including in places outside the Gulf like Amman, northern Iraq, and Lebanon.

This problem is compounded by poor public transportation systems in most of the region’s big cities, which make it hard to commute to work from suburban areas. People living in cities like Cairo, Baghdad and Tehran will often settle for less secure tenure arrangements in overcrowded neighbourhoods in order to be able to get to work. Prindex findings support this pattern, revealing that people living in urban areas on lower incomes tend to feel more insecure.

Our findings suggest not only a need for policies that provide secure housing, especially for vulnerable groups like displaced people, women, and low-income households, but that prevailing cultural practices and traditions need to be challenged. Some states are reforming their laws to ensure the dignity of their citizens, while others seem to be waiting for a miracle. In the end, Prindex’s comparative data may show policymakers which of these two approaches is working in the eyes of their citizens.