It’s Just Architecture! The Venice Biennale Architettura 2021

“We need a new spatial contract”, says Hashim Sarkis, curator of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition, inviting participants from all around the globe to ponder sustainability and the question ‘How will we live together’. But how just and sustainable can architecture truly be? A critical review by Aseman G. Bahadori

“If architects are asking how ‘How will we live together?’, there is a feeling behind it of culpability, for not having raised the question earlier.”

It is on my fourth day, and in the very last week, of the 2021 Venice Biennale Architecture that I stumble upon this quote by Bruno Latour printed on one of the monumental walls in Giardini’s Central Pavilion. A sentence that deeply resonates with me. This year’s curator Hashim Sarkis invited architects to “imagine spaces in which we can generously live ‘together’”. As a political and social scientist, to me, the entire theme of the Biennale begs the sincere question of what architects have been tasked with until now – with the contemplated focus on ‘togetherness’ insinuating a tale of division. So, what is architecture about, then?

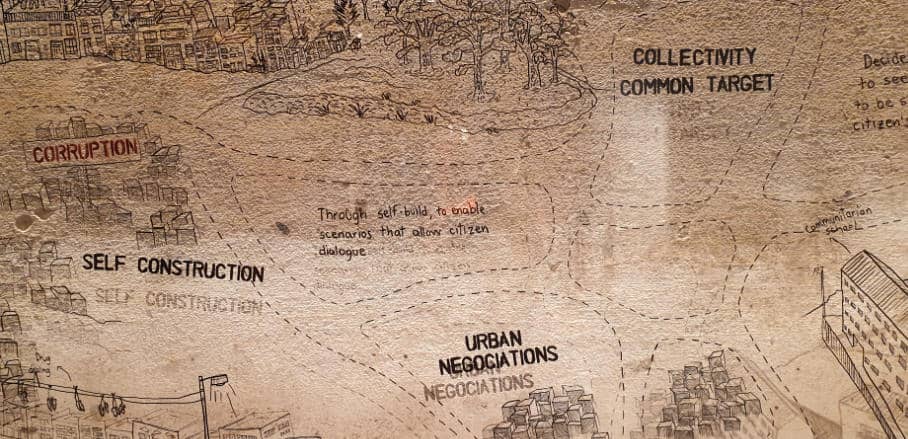

“Tactical and Peripheral Architecture”. By Ana Maria Lopez Ortego, Harold Guyaux, Felipe Gonzalez González, and Viviana Parada Camargo © Aseman G. Bahadori

What is the Essence of Architecture?

Architecture, in its very essence, is about applying technical skills and knowledge to plan the built environment. Typically, architects don’t build themselves, but are invited or commissioned to design spaces; or according to an official definition: “The defining skill of the architect is design – the ability to conceive of, and elaborate on, physical artefacts that meet human needs and evoke aesthetic response”. It is this essential focus on human needs and values that elevates the technical description of this profession onto another dimension – as architecture is just as much a deeply intellectual and ethical practice.

Thinking about the spatial dimensions of our world means you need to think about the social conditions of the spaces we plan, build, and ultimately inhabit. How do we want to live together? How do we design meaningful spaces for human connection? What are dignified ways of co-existing on this planet, amongst humans and with other beings?

Accordingly, it should be impossible to separate these questions and their socio-political negotiation from the purely spatial and technical engagement with design. In theory, at least.

“What We Share. A model for co-housing” in the Nordic Pavilion is a full-scale section of a prospective co-housing project. Helen & Hard Architects, Anna Ihle. © Aseman G. Bahadori

Sustainable Design – Does it Exist?

Many have pointed out that sustainable, green, or resilient architecture often does not deserve that name. Whether it’s not actually planning for the recyclability of materials, resulting in a form of architecture where “buildings are designed to be built, but not designed to be deconstructed”; or merely looking at energy efficiency and not embodied carbon; or not fully understanding the carbon footprint of the materials we use. Even with wood, a carbon-friendly, regenerative material, celebrated as the “silver bullet we have been searching for”, there are concerns regarding its supply, as preserving our forests is one of the most important measures to mitigate the effects of climate change.

But I want to hear from architects themselves, preferably the ones that actually do work in large architectural firms and are entrusted with planning the very fabric of our cities. Luckily, I am accompanied by such a group of architects from one of Germany’s ‘star’ architecture bureaus, headquartered in Berlin. As we admire stunning projects from around the world in the cold halls at Arsenale, in the winding waterways of Venice, or over a hot cioccolata by the outdoor country pavilions at Giardini, I ask around: what and how much can architecture and design contribute to just and sustainable cities – really?

Having survived Earth’s abrupt shift to an era of precarious climate, a multispecies community gather in the blasted ruins of modernity to find new ways of living together. “Refuge for Resurgence” by Anab Jain, Jon Ardern, and Sebastian Tiew. © Aseman G. Bahadori

A Biennale of Dreams – And a Reality Check

Matthieu, a young architect, seems conflicted: “Yes, the projects here are wonderful. But they also make it look so easy: attach a bit of green and some paper trees on this model, build a sustainable house at a very small scale in that model, and there you go, architecture is sustainable. But how can I actually implement this in reality? Especially when our budgets are so incredibly tight, and our investors are first and foremost interested in making a profit?”

It is true that the Biennale is characterised by an experiential and artistic urge to find answers to the most pressing questions and concerns of our time, such as “Refuge for Resurgence” (Superflux), a multi-species banquet set after the end of the world.

It seems that you must be visionary, even utopian, to find solutions in times that make it all too easy to be pessimistic. In other words: money and budgets, and for better or for worse, even reality, often don’t play a role here. Nia, another colleague, adds: “Events such as this are important as it is a space for projection and raising awareness. It reminds us at least of what architecture should be about in the first place”. And, indeed, the exhibition presents many such reminders.

Installation by Fanhao Meng. “Mud stove family” in Dongziguan village © Aseman G. Bahadori

The Architect of the Future

Architect Fanhao Meng answers this year’s theme with a vision for urban-rural integration in China in the installation “Rural Nostalgia | Urban Dream”, a large 1:30 physical street model of Dongziguan village. The affordable housing project included the perspectives of its villagers to address their needs through investigations and meetings before construction.

The curatorial team of the National Pavilion UAE looked at sustainable resources for construction, intending to replace cement. Cement production accounts for about 8 per cent of global CO2 emissions, and concrete, a derivative of cement, is the world’s most-consumed material after water. Their efforts won them the Golden Lion Award for Best National Participation, the exhibition’s highest honour. Inspired by sabkhas, naturally occurring salt flats in the UAE, and materials such as karsheef (a traditional building material made from salt and mud), “Wetlands” is a large-scale prototype structure created from a new, environmentally friendly cement made of recycled industrial waste brine.

“Wetlands”, National Pavilion United Arab Emirates, curated by Wael Al Awar and Kenichi Teramoto © Aseman G. Bahadori

Yes, the Biennale provided us with impressive examples of how architecture is so much more than designing buildings and spaces, how it is rather about meaningful placemaking. In the words of Dr Craig L. Wilkins, one of the first theorists on Hip Hop Architecture, in his short essay ‘The age of the architect activist’: “One of the driving forces of the twenty-first century will be extending design beyond merely the creation of objects of desire into the areas of economic, social, and environmental justice […] away from referring to the visual aesthetics of buildings alone to include their visible ethics as well”. This exhibition asks architects to do just that by taking ownership and responsibility.

Setting the Stage For a New Era

Circling back to our initial thought, I wonder: do architects have something to feel guilty about? I could not possibly attest to a lack of reflection or awareness, but something still seems amiss. As Leon points out: “As architects, we love to ask ourselves all day long how people can live and come together. Even if we have little power, we truly believe it’s our job! But at the end of the day, it’s the investors who decide. And for them to invest in a more sustainable and equitable future, our governments need to exert much more pressure.”

Leon, an aspiring architect from Germany, explores the herbs and greenery at “con-nect-ed-ness”. By Lundgaard and Tranberg Architects in Denmark’s National Pavilion. © Aseman G. Bahadori

In conclusion, as important as it may be to look at the architect as the “convener and custodian” of a much-needed new spatial contract, architects’ dream of a better future cannot and should not be achieved alone. Considering the reality of the building and construction sector, it is thus surprising to see the exhibition’s lack of drastic and urgent political commentary on this specific set of topics: money, investors, developers, capital, and the state.

In times of social upheaval, conflicts, climate change, and inequalities, the Biennale proves that architects everywhere are already transcending the architecture-as-art paradigm. But the very environment in which the architect needs to operate must be questioned much more, for her to co-design a better world. After all, it’s not ‘just’ architecture.

- It’s Just Architecture! The Venice Biennale Architettura 2021 - 22. December 2021