Equitable Public Spaces in Latin America: A How-To

Public spaces and public life in South American cities are dominated by car-oriented planning. Organisations like Chile-based Ciudad Emergente aim to change this through tactical urbanism.

Mobility patterns like those of Santiago de Chile, where about a third of the population use private cars as the main transport mode, are a trend replicating across many other Latin American cities: in Lima, 51 per cent of people spend over two hours in traffic jams daily; in Mexico City, people spend an average of 18 days a year stuck in traffic. In the same vein, the vibrancy of public spaces as hubs of community life is under threat. Decades ago, children and families might have made use of the space in a different fashion, such as playing football in the streets, picnics in the plazas or storytelling time between family members and communities, but now streets are congested thoroughfares or empty pavements used as parking lots.

As the Danish urbanist Jan Gehl notes, if we design streets for cars, we end up with streets taken by cars. Cities in Latin America face the both challenge of how to revert this trend, and of how to revalue our cities. But this picture of car-centric cities does not fully represent the positive efforts underway in many municipalities that are revitalising public spaces and taking advantage of community participation in the process. How exactly are they doing it?

Tactical Urbanism’s Moment?

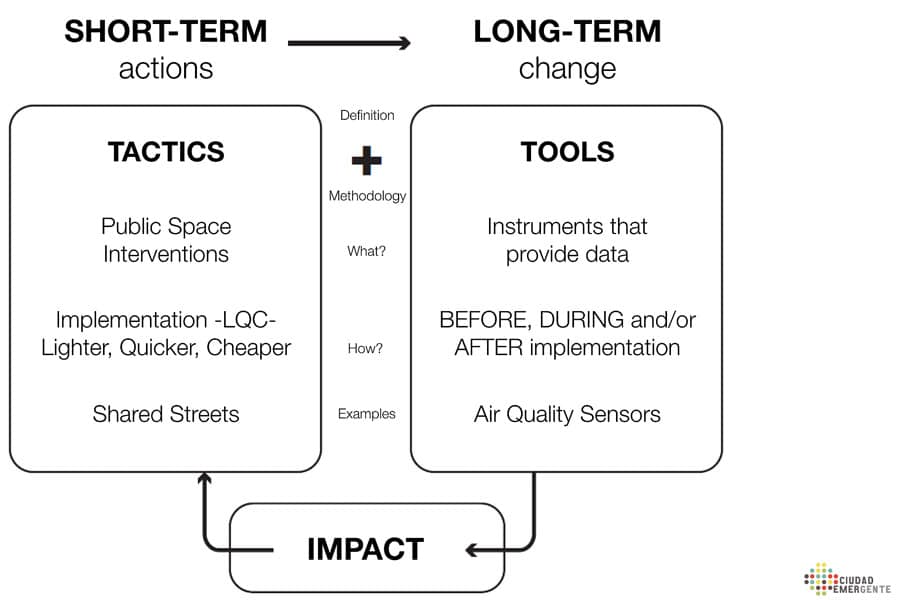

In the last decade, South American cities have deployed the concept of tactical urbanism to transform public spaces into more equitable and just landscapes. Initiated about a decade ago by the so-called Next Generation of New Urbanism, led by the Street Plans Collaborative, tactical urbanism uses short-term actions to leverage long-term changes. Tactical urbanism offers an innovative and inclusive method to integrate local communities into the transformation of streetscapes and the revitalisation of public spaces.

In Latin America, the Chilean non-governmental organisation (NGO) Ciudad Emergente has applied these methods in over ten countries, highlighting the value of well-implemented tactical experiments complemented by tools for data collection to provide evidence-based approaches to planning processes.

Figure 1. Tactical urbanism process.

This combination of tactics and tools offers a means to leverage long-term changes and sustained impact for an equitable distribution of public space. Here are some examples of how this method works.

Shared Streets as a Tactical Strategy

In 2019, bike lanes enacted on Calle Portugal in Santiago Centro registered a 560 per cent increase of cyclist demand compared to 2016, as data from the local Mobility Taskforce shows. How did this happen? In 2016, a tactical action called Shared Street for a Low Carbon District was piloted by Ciudad Emergente. During the tactical intervention, the street was partly closed for cars, and sidewalks were expanded enabling local businesses to use the street as an extension of restaurants, and families and communities were able to walk and cycle safely. The experiment’s result was a one-kilometre temporary bike lane connector, together with a transformation of the city landscape – from a conventional street for cars, to a street for people and cars.

Sponsored by the Municipality of Santiago, it included the local community in the process: citizens’ opinions were collected by Ciudad Emergente and handed to the Municipality as evidence of what the community aspired for in the neighbourhood. Moreover, trust building to facilitate communication was encouraged between local authorities and the community throughout the intervention.

This also supported broader planning processes and neighbourhood discussions, easing communication between local government officials and community leaders, even during a later political administration change. The combination of hands-on planning experiences, together with the data collected throughout the intervention, helped bootstrap a permanent investment in bike lane connectors in the neighbourhood.

Before the intervention, 800 cyclists rode the area per day. After the construction of the permanent cycling lane, 4,500 cyclists were registered by daily bike counters, demonstrating that demand increases with access to safe cycling infrastructure.

Shared Street tactic in Santiago de Chile, 2016 © Rodrigo Fortuny/Ciudad Emergente

Opportunities After Covid-19

Such experiences are not bound to Santiago. Similar experiments involving local communities in the development of public spaces occurred in Comayagua (Honduras), Mexico City, and Panama City. Such actions are led by a wide range of actors, from NGOs to city officials. The benefits are multiple, from improving air quality to empowering social and community engagement.

In 2018, Danlí, Honduras, expanded the Shared Street model: tactical actions led to the city’s first “critical mass” bike ride, creating a momentum for systemic change represented by a new awareness for pedestrian and cycling infrastructure coming from Danlí’s communities and other Honduran local governments and Universities. The Danlí implementation was conducted under a tactical urbanism knowledge transfer project sponsored by the United Nations Development Programme and the Fondo Chile Grant. This in turn provided a model for other Honduran cities such as Tegucigalpa and Comayagua, which enacted similar transformations for more just and equitable cities. In 2019, the city of Comayagua started the design of the first Sustainable Mobility Plan (Plan de Movilidad Urbana Sostenible or PMUS) with the support of the Spanish and Andaluzia International Cooperation Agency (AACID) and Ciudad Emergente, using tactical urbanism methods.

Shared Street tactic before and after, Panama Camina © Javier Vergara Petrescu/Ciudad Emergente

With Covid-19, Latin American cities are struggling with extreme vulnerabilities, while at the same time recognising the needs and benefits of such tactical methods to accelerate more equitable and environmental changes in their cities:

Bogotá, Colombia, has implemented over 35 kilometres of new bike lanes in 2020. Rancagua and Arica, Chile, have witnessed seemingly overnight changes, from streets for cars to streets for people. Changes that, before Covid-19, would have taken years to enact.

After a decade of tactical urbanism, this moment offers a unique opportunity for cities to embrace and own change. The predominance of car-oriented urban planning is often rooted in a lack of vision of what a sustainable city can offer. The current health crisis underscores the urgency for a much greater transformation of our cities. Luckily, we have the tools, as well as communities who are open to change. Now is the time for change, with the opportunity to be bold and to implement our visions on a major scale.

- Equitable Public Spaces in Latin America: A How-To - 30. July 2020