Landscape Porosity: Why we need Water-Based Urbanism

Creating urban spaces that allow for the free flow and penetration of water and wind is essential to the survival of water-based cities like Bangkok. “Landscape porosity” can help us better understand and defend these urban ecosystems in times of climate change, says Kotchakorn Voraakhom.

By 2050, rising sea levels could affect triple the amount of people previously predicted, threatening to all but erase some of the world’s great coastal cities including Bangkok. Southeast Asia, the region with the largest total coastline in the world, is facing extreme risk. Its cities, rooted from agrarian, water-based societies, have now transformed into paralysed concrete developments, leaving many delta capitals under extreme water stress. The need to shift away from concentrated land-based development is apparent.

“Landscape porosity” proves to be a useful approach by looking at how we can reclaim a city’s porosity, especially in the context of muddy delta cities. Porosity can be understood in this context as a city’s capacity to adapt to the natural flow of water, focusing on fluidity and flexibility as essential mechanisms of climate adaptability – elements often neglected in urban development.

Breathable void and healthy pore structures, allowing for the flow and penetration of water and wind, are thus key necessities. It is the mission of the Porous City Network (PCN) to defend these ecological pore spaces while creating more through trees, parks, green roofs, forests, wetlands, ponds, and grasslands. In this regard, Bangkok serves as an excellent example of how building eco-centric green and blue infrastructures can revive our cities’ urban ecosystems.

The City of Water: Past, Present, and Future

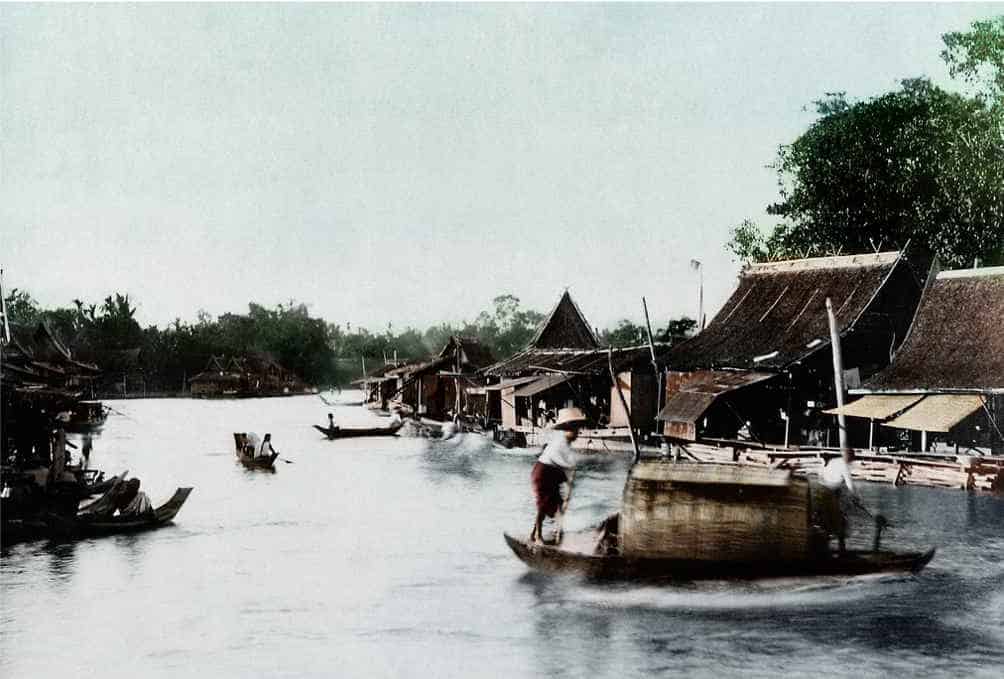

© Siam Renaissance, 2010. / Athada Khoman

Sitting on the floodplains of the Chao Phraya River, Bangkok’s geography is greatly dominated by the three hydro-ecological characteristics which gave it its symbolic name, the “City of Three Waters”. The delta landscape of Bangkok and Central Thailand is formed by the rivers, the rain and the sea. This terrain proves incredibly essential to life as much of Bangkok’s culture, and Thai history itself, is deeply interwoven with the natural cycles of water.

But only after half a decade of rapid urban development, life in water communities has tremendously waned. Many canals are now filled up for new developments or replaced by new roads, whereas many others became stagnant and non-navigable, reduced to drainage ditches and open sewers which in turn create hardships for many farmers who rely on these waterways. As urbanization increases at an alarming rate, Bangkok’s lower delta has forgotten its waterscape community and its ability to adapt.

The three hydro-ecological elements once considered vital and a blessing for the land and its people, now pose a sporadic climate disaster in forms of severe flooding and extreme drought, as well as subtle changes underway through saltwater inundation. In 2011, when the “City of Three Waters” was unwilling to get wet, the consequences proved disastrous. Heavy rains flooded the Northern part of the country, trying to flush out to the ocean, only to be blocked from passing through Bangkok, the lower delta where the estuary lies.

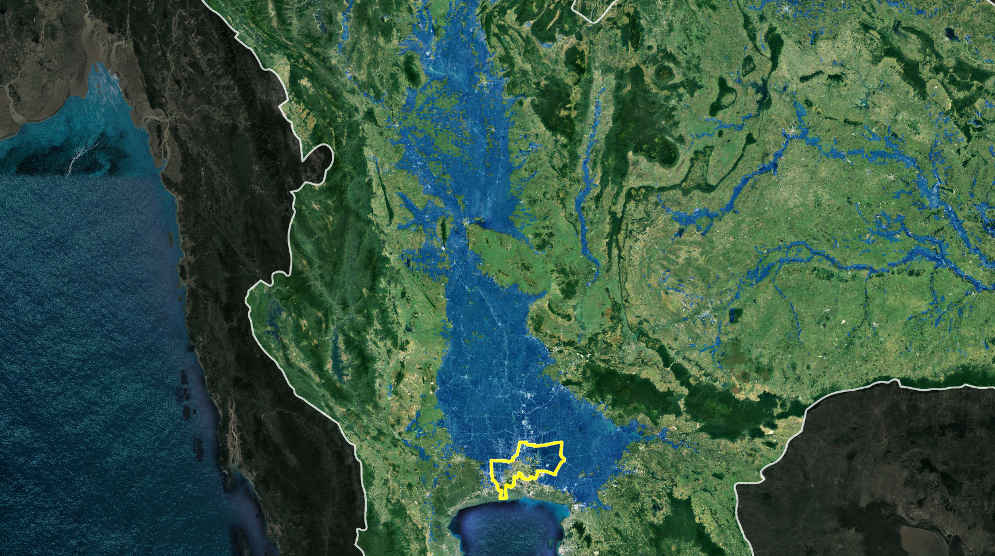

Flooding 2011. © LANDPROCESS /Data : RADARSAT-2, 2011 / GISTDA

Instead the floods were contained longer in upstream provinces, keeping the capital from getting wet. In the end, it killed more than 800 people and affected over 13 million, becoming the most expensive disaster in Thai history. In fact, Bangkok’s modern land-based infrastructures, its concrete development, dams, and roadways, have rendered the land incapable of adapting to the natural flow of water; and when surges from the sea, rainfall, and flooding from the north all arrive at once, this worst-case scenario can happen all over again.

Porous Landscape Innovations – the Porous Park

To address diminishing landscape porosity, every square meter is needed to reclaim resilience for the land to live with water, rather than fear it – especially in Bangkok, a capital that once breathed and absorbed water and has now one of the lowest in public green space ratios.

Porous landscape innovations can provide a much-needed answer. For the first time in 30 years of rapid urban development, an invaluable property in the heart of Bangkok—11 acres of land and 1.3 kilometres avenue to be exact — was not turned into another space for commercial use. Instead, it was transformed into a public park. Opened in 2017, the Chulalongkorn Centenary Park is the first critical piece of green infrastructure in Bangkok to mitigate detrimental ecological issues through landscape porosity. Bangkok is a flat city. By harnessing the power of gravity, this park sustainably collects, treats and holds water to reduce urban flood risks in its surrounding areas – featuring sustainable drainage systems, a green roof, wetlands, and a retention pond.

Sitting on a three-degree gradual incline not a single drop of rain is left wasted. The rain and runoff are pulled down through the park‘s topography to generate a complete water circulation system, which can hold up to a million gallons of water during heavy rainfall. While playing a role in confronting climate risk, the park also serves as an outdoor classroom and recreational space for the university community and its surrounding neighbourhoods. Following the concept of urban forests, 300 varieties of plants and 5.000 trees were grown, recreating a healthy ecosystem and increasing urban biodiversity by providing a home for 30 more species of local birds, pollinators and insects.

Chulalongkorn Centenary Park © VARP Studio

Waterscape Urbanism as the Way Forward

How many porous parks do we need to sustain and prevent a city from flooding? The answer does not lie in the number of parks, but in permanently returning to our natural waterscape. This is not an option – it is the only way to survive. Understanding our historical resilience and adaptive living with water is evident in the indigenous processes that are crucial in waterscape urbanism needed for Bangkok’s future on the Chao Phraya River delta. To keep our water-based city afloat, we must start by revitalizing our canals, floodplains and once porous lands to align them with our development as we move forward.

Urban development is inevitable, and the population is bound to rise, while climate change remains an enigmatic puzzle to solve. But it is our obligation to consider every possible solution and sign of hope for our future. The Chulalongkorn Centenary Park gives us a spark of inspiration in how we can choose to handle our future challenges, while allowing room for new landscape porosity innovations to emerge.

- Landscape Porosity: Why we need Water-Based Urbanism - 28. April 2020