Making Cities Safer for Women and Girls, Part II

This is the second part of the article. Read Part I here

Women working with the city to increase safety in public spaces

One of the foundations of the women’s safety movement has been to show that women are experts in their own safety, and should be empowered to take part in local decision-making. The “Take back the night” movement, developed in the 1960s in Europe and North America, was designed to raise awareness of sexual violence against women and girls (SVAWG), reclaim public spaces and demand safety on public streets. In Canada, in response to a series of sexual assaults and murders of women in Toronto in the 1980s, local community groups, academics, and others lobbied the city and local police to improve women’s safety. The city responded by creating the Metropolitan Action Committee on Violence Against Women and Children (METRAC), to address public violence against women and children in 1984, which subsequently developed the Women’s Safety Audits Process in 1989.

The women’s safety audit tool is now used in communities worldwide. It uses a participatory approach to enable direct communication with city officials and civil society groups. Initially developed around situational concepts of crime prevention, it involves groups of women and girls walking around public spaces in their neighbourhoods, often with a city official or police representative, to identify the areas that feel unsafe. The findings are used to develop recommendations for the city. Responses to the issues exposed during the audit can range from costly long-term improvements, to inexpensive ones. For example, the recommendations from an audit by a group of elderly women in Gatineau, Canada informed the upgrading of a park. Improvements can be as simple as installing hand painted signs with street names, as occurred in an informal settlement in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The safety audit tool thus empowers women within communities to provide their personal expertise and lived experience as a resource to the city. What is significant here is that women work with the cities, making a real impact and effecting positive change.

Since the 1980s interest in women’s safety has expanded in cities in many countries around the world. Crucial to the advances that have been made, is the interdisciplinary approach to thinking about gender and the city. Criminology, crime prevention, political science and governance, urban planning and design, social change and community development all need to be included in the discussion if cities are to become safe places for women and girls. New tools and innovative approaches have been developed to increase public awareness, and the reporting and mapping of women’s safety, and some of these are discussed below.

Arts and campaigns

Raising awareness is one of the first steps to building support and mobilising key stakeholders to work to reduce and prevent violence and the threat of violence against women and girls (VAWG) in public spaces. Art is one powerful way to bring attention to harassment and VAWG.

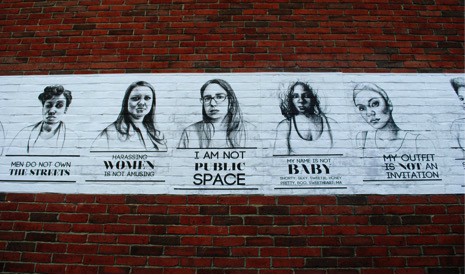

For example, the Brooklyn-based artist Tatyana Fazlalizedeh’s ‘Stop Telling Women to Smile’ is a series of portraits of women with captions denouncing the public sexual harassment they experience. Her work has appeared in city streets in Mexico, the USA, Canada, Germany, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Another example is the ‘Women on the Walls’ initiative launched in Egypt during the Arab Spring of 2013, which used graffiti and street art to raise awareness about women’s issues and rights in an effort to empower Arab women. The initiative also encourages a stronger female presence on the streets of Egypt by supporting female graffiti artists, and is now a growing network of artists throughout the Middle East. In Rosario, Argentina women and girls designed and painted a mural in a neighbourhood square they identified as unsafe. The mural was a way to re-appropriate public space with its message: ‘More women in the street. Cities safe for everyone without fear and without violence’.

Technology and crowdsourcing

Technology is having a profound impact on women’s ability to raise awareness against sexual harassment, report assault and unsafe areas, share personal stories, and mobilise across cities and international borders. It helps to empower women to stand up for their right to safe public spaces. The increased affordability, accessibility, and availability of smart phones, and use of the internet and mobile devices has changed communication dramatically. Numerous mobile applications and websites now allow users to report and share their stories anonymously. Hollaback!, Stop Street Harassment, the Everyday Sexism Project, and the Translink Harassment Blog, for example, all offer a platform for women and girls to share and validate their diverse experiences of sexual harassment safely and anonymously. The wealth of responses lets users know they are not alone, and provides extensive data on the incidence of VAWG that are not reported to the police, as well as the type of aggression and where it occurs. In 2014 Hollaback! partnered with Cornell University to perform the largest analysis of street harassment to date, and has more recently partnered with universities, cities, and specialists around the world to analyse their data and uncover trends. This enables cities and others to draw informed conclusions about the extensiveness and location of street harassment.

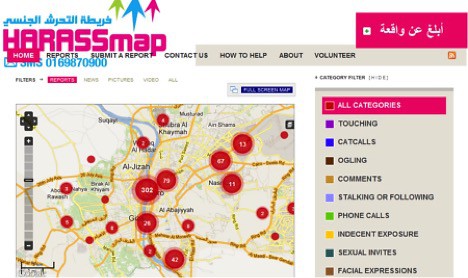

Another important development is the use of mapping and geotagging to report incidents and notify other women of unsafe areas. For example HarassMap can be used by victims and witnesses to report what happened and where. The app was originally developed for use in Cairo, but now cities around the world are developing their own versions.

Safetipin is another mobile app that uses a map-based platform. Originating in Delhi, the app provides an electronic version of the safety audit tool that can be used on a smart phone, and shares information through a map. Safetipin is being used quite extensively in different cities, and is now working with municipalities to help them develop policy responses to the data collected.

The internet is also a useful tool for mobilising women and girls. The “Girls at Dhabas” was initiated by two Pakistani women in an effort to reclaim public spaces in South Asia. They use Facebook, twitter and Tumblr, with the hashtag #GirlsAtDhabas, to share photos of girls at dhabas (roadside tea stalls typically occupied by men), playing cricket in the street, loitering in public places, and generally enjoying public spaces which are stereotypically occupied by men, encouraging other women and girls to do the same.

Urban planning for women’s safety

The women’s safety audit has been an important tool for documenting women’s relationship with the built environment. However, planning for women’s safety also requires good urban governance, with women taking part in neighbourhood and city decision-making processes.

Gender is a cross-cutting issue that touches many areas of municipal planning, so it is important that city plans are gender mainstreamed, rather than considering gender as a secondary issue. Women and girls need to plan with the city and not be planned for. The city of Vienna, Austria is recognised as a model city for incorporating gender mainstreaming in urban planning. In 1991 a group of city planners organised a photography exhibition titled “Who Owns Public Space – Women’s Everyday Life in the City,” depicting women in Vienna. The exhibit received so much media and public attention that politicians have since undertaken over sixty pilot projects and produced many guides on mainstreaming gender in urban planning. Seoul, South Korea is another excellent example of a city that has incorporated gender mainstreaming into their urban policy through a two-track strategy of systemisation of policy measures for women, and in-depth gender analysis.

Improving urban services

Women’s and girl’s safety and inclusion in the city also depends on how well those delivering urban public services are trained on gender issues. In Latin America, the NGO Red Mujer y Habitat is working to strengthen collaboration with the police, providing them with training on gender equality and women’s right to the city, and on dealing with cases of VAWG. As part of Plan International’s Safer Cities for Girls Programme, Women in Cities International (WICI) developed a training module for municipal governments on girls’ safety and inclusion. Adolescent girls who participated in the programme received training on how to engage with municipal stakeholders, not only to share their experiences, but to speak out on the issues most important to them. This two-pronged approach offers both municipal stakeholders and adolescent girls the tools they need to address common challenges together, empowering girls to participate, and teaching the city how to listen and adapt its services.

Concluding thoughts and looking forward

Building on work that began in the 1980s in Canadian cities, it is evident from the above examples of action research and campaigns around the world, that creating safer cities for women has now truly grown into an international movement. There are now several global initiatives aimed at ending VAWG in public spaces, including the UN Women Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces programme, now being implemented in over 20 cities from the global North and South. A diversity of women and girls are at the centre of these efforts.

Today the movement for women and girls safety is strong. It is not only a story about women being protected from violence, but also about the empowerment of women and girls to participate in public life and access urban services. Achieving this demands multi-level, multi-sectorial and multi-stakeholder engagement. We will have to face and overcome new challenges where VAWG is present, since it is often not well studied or understood. VAWG in the context of migration, refugees, climate change and on the internet are some examples. Confronting these challenges as well as the ongoing challenges of making urban public spaces safe for all women and girls requires an intersectional analysis to understand the nuances with which different groups live and experience safety in the city. UN-Habitat has also argued for a more holistic and multi-dimensional approach to urban safety and security enriched through “effective urban planning, design and governance from a gender perspective in cities”.

The concept of women’s safety has expanded from concerns about sexual harassment or assault in public spaces, to being empowered to move about freely and access the city as a right, as well as freedom from poverty, and financial and housing insecurity. Henri Lefebvre and David Harvey’s concept of the “Right to the City,” argues for women to have the right to use the city and to participate in its creation and re-creation, building on the belief that gender equality is a human right.

There is a need for transformative policies at all levels of government, and meaningful implementation on the ground that supports gender equality from an intersectional perspective. This requires continued improvement of data collection, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes to assess impacts, the integration of gender mainstreaming, budgeting at city level, and increased public awareness. It is vital that we create gender inclusive built environments and physical infrastructure, accompanied by urban policies and programmes that create opportunities for women’s meaningful participation in shaping urban governance and development.