Community Engagement in Accra: Playgrounds Meet Markets

With children spending their days at their parents’ market stalls, how can we turn markets into safe places for them, where they are free to learn and play? Amowi Phillips from the Mmofra Foundation shares an inspiring example of community engagement in Accra, Ghana.

Children’s Presence in Accra’s Markets

In West African cities like Accra, Ghana, women have historically been key operators in the marketplace, not only as overall managers, wholesale distributors and retail vendors at every scale, but also as the principal customers. With great resourcefulness, they negotiate these intense commercial environments where social and economic dynamics are complex and fluid.

The children they care for are also a presence in the public market that is hard to miss. Every day, thousands of children spend several hours in urban markets with mothers and caregivers who ply their trade with one eye on their charges. The youngest may be tied to their mothers’ backs with lengths of cotton cloth whilst the under-fives are clustered in small play groups in the backs of stalls. After school, older children find their way to their family members’ places of business to eat, help with market or childcare tasks, and do their homework.

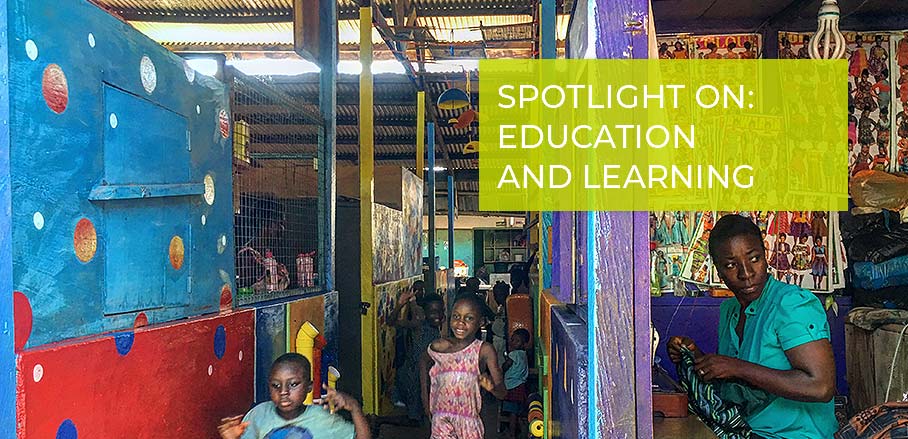

Playing in the market, Mallam Atta Market, Accra, Ghana © Mmofra Foundation

Pairing Markets and Parks

Away from the bustle of markets, in the heart of Accra’s Dzorwulu districtis one of the rare privately owned yet publicly accessible green spaces in the city: an acre-sized park stewarded by Mmofra Foundation, an advocate of playful, enriching environments for children. Working at its design, our talented team brought artists and artisans together in an experiment to adapt ordinary and cheap materials from nearby markets for playful outdoor learning.

This unlikely pairing of markets and parks yielded a treasure trove of insights as well as materials for repurposing during many excursions along market alley-ways, where our vendor friends were happy to procure for us quantities of the wooden utensils, gourds, giant seeds, and basketry that were integrated into play features in the park. They politely accepted our invitation to bring their children to the park although the challenges of mobility and spare time would make this impractical.

From this experience rose the idea to turn the market itself into a playful space; we figured this was an idea we could at least prototype, building on the relationships we had already established.

Community Engagement is Essential for Successful Interventions

The physical infrastructure of Ghana’s hundreds of urban public markets ranges from informal groupings of stalls and kiosks to solid structures of several storeys. However, women’s control of the market culture is similar everywhere. The fact of children in the market is unlikely to change soon, yet it is far from a child-friendly environment.

Twelve community members in their teens and twenties took part in a playful market design workshop. These young women and men were raised in and around two of the major markets in Accra. They helped us understand how safe walkways, lighting, and shelter from rain were an integral part of playful intervention. We learned from them how, spatially and conceptually, the informal and often intimate scale of the market requires sensitive observation of routines and flows in order to plug into an existing ecosystem without disrupting its function.

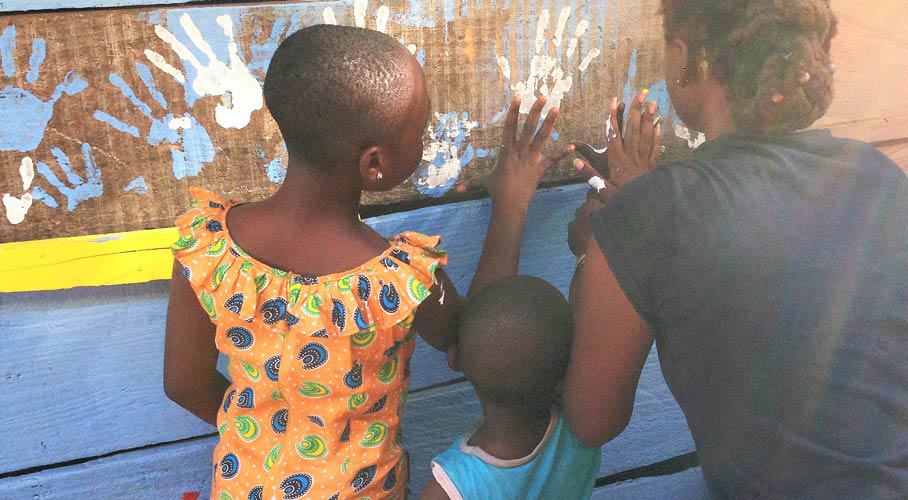

Playing in the market, Nima Market, Accra, Ghana © Mmofra Foundation

Once completed and in use, our prototypes served as demonstration sites for hundreds of market users. Our observations will feed into the next iterations of playful markets:

- Children are natural placemakers. Children learn by exploring their environments, and in doing so, they can teach the observant designer a lot about what works in public spaces. In the Accra markets, many young children spend the day around mothers and carers –with no accessible, child-friendly space available, parents would rather keep them within arm’s reach. Once we began constructing our playspaces, we noticed a shift, as children started engaging with the new structures even while they were being built! The positive feedback was clear: children in the city value having interactive, purpose-built spaces of their own.

- Child-friendly design and positive economic impact go hand in hand. In urban commercial spaces, we can demonstrate both the social and the economic value of child-friendly design. Converting a commercial space into a play area could be perceived as a risk for business. Recognising that concern, we sourced building materials from market vendors, and worked with community leaders to keep resources circulating locally. The finished spaces have a net positive financial impact, and even attract new customers.

- Existing spaces can be transformed for play with a flexible and frugal approach. By adding interactive features to existing structures, we create new layers of functionality for children while maintaining the original purpose of the space. We considered market stalls and their use patterns as the most obvious scaffolding for creative additions. We painted walls and floors, suspended artworks from ceilings, and installed interactive structures to encourage motor coordination skills. Market users saw these interventions as enhancements, rather than interruptions to the normal flow of daily commerce.

- Culturally informed placemaking is critical for children’s socio-emotional development. The sounds, textures, colours, and movements that define the daily lives of children are essential sources of inspiration for playful intervention.Cultural framing during the design process benefited greatly from the intensely sensory and vibrant environments of markets in Ghana. By repurposing ordinary domestic wares like wooden ladles, calabashes and seeds into play structures and visually stimulating installations, we introduced elements of magic into a familiar world.

- Community buy-in sustains the placemaking process. With a holistic exchange of information among constituents, the intervention leaves an imprint for the community to define, take ownership, and inhabit. We encouraged conversations among market leaders, caregivers, children, artisans, and educators, validating the importance of child-friendly spaces for each group. Once persuaded of the beneficial impact of this placemaking, adult community members became advocates in their own right and built alliances to ensure the continuity of the space beyond the lifetime of our project.

Market Collage © Mmofra Foundation

The project described in this article was supported by Healthbridge Canada and UNHABITAT.

- Community Engagement in Accra: Playgrounds Meet Markets - 27. January 2022