Hotspot Cities

By Richard J. Weller

With Research assistants

Chieh Huang, Claire Hoch, Zuzanna Drozdz, Sara Padgett Kjaersgaard, Nangxi Dong

In the UN Convention of Biological Diversity, 196 nations have agreed to put 17% of the earth’s surface under protection. Author Richard Weller calls for additional land to be protected in the world’s “hotspots”, where biodiversity is threatened by urban sprawl. In his text, he discusses why regional ecology is an issue for urban planning.

In 1970, there was a global total of 2.5 million km2 of protected area[1]text. Today, there are about 32 million km2 (20 million terrestrial and 12 million marine). Under the guidance of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the world’s conservation NGOs, along with their local partners and networks of donors, can duly take credit for creating this extraordinary global estate. But they are not finished yet.

Under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”URBANET” suffix=””]196 nations have agreed to achieving 17% global terrestrial area as protected area by 2020.[/inlinetweet][2]Convention on Biological Diversity, “List of Parties,” accessed June 1, 2016. 196 nations are party to the Convention on Biological Diversity. 28 of these have not yet signed the Convention so as to make its terms legally binding. With about 15% of the earth’s terrestrial surface already under protection, an extra 2% might seem trivial. But 2% of the earth’s land represents more than 700,000 Central Parks, which, laid out end-to-end, would run 70 times around the world! The question is, where should additional land be protected?

Increasing urbanisation puts biodiversity at risk

To answer objectively, my research assistants at the University of Pennsylvania and I have published an Atlas which audits land use in the world’s hotspots, 36 regions around the world more or less agreed upon by the scientific and conservation communities as the most important, most diverse and most threatened biological places on Earth[3]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biosphere_2. The same way our libraries store and protect culture, hotspots store life’s genetic inheritance.

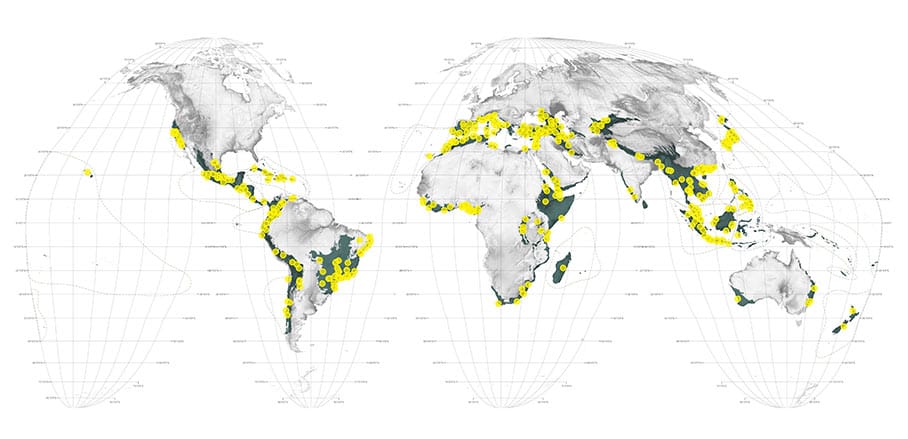

Map of the world’s protected areas showing the biodiversity hotspots in brown. © Richard Weller

If we apply the global 17% target to each hotspot, we find that 21 of 36 fall well short of achieving 17% protected area. What’s more, we’ve found that of the 422 cities (population centers of 300,000 or more people) in the hotspots, 383 are growing on a direct collision course with endangered species. This is not just a little bit of sprawl. Let’s say an extra 3 billion people move into cities by 2100, as is entirely likely, it means the equivalent of 357 New York Cities will be constructed in the next 84 years. That’s 4.25 additional New York Cities per year. Much of that growth will eradicate biodiversity.

Map showing which hotspots currently fall short of 17% protected area and the cities which are on collision courses with remnant habitat and endangered species. © Richard Weller

Why does this matter? First, just as we value our own lives we can assume that all other forms of life are intrinsically valuable, even if we do not know ultimately why. Second, we can perhaps agree that humanity is metaphysically more fulfilled when living in environments replete with diversity. Put another way, in a rainforest your senses are heightened, whereas in a corn field they are dulled. Third, biodiversity is not just about charismatic megafauna (pandas) it is a register of the overall health and resilience of an ecosystem upon which our cities ultimately depend for their sustenance.

Regional ecology: An issue for urban planning

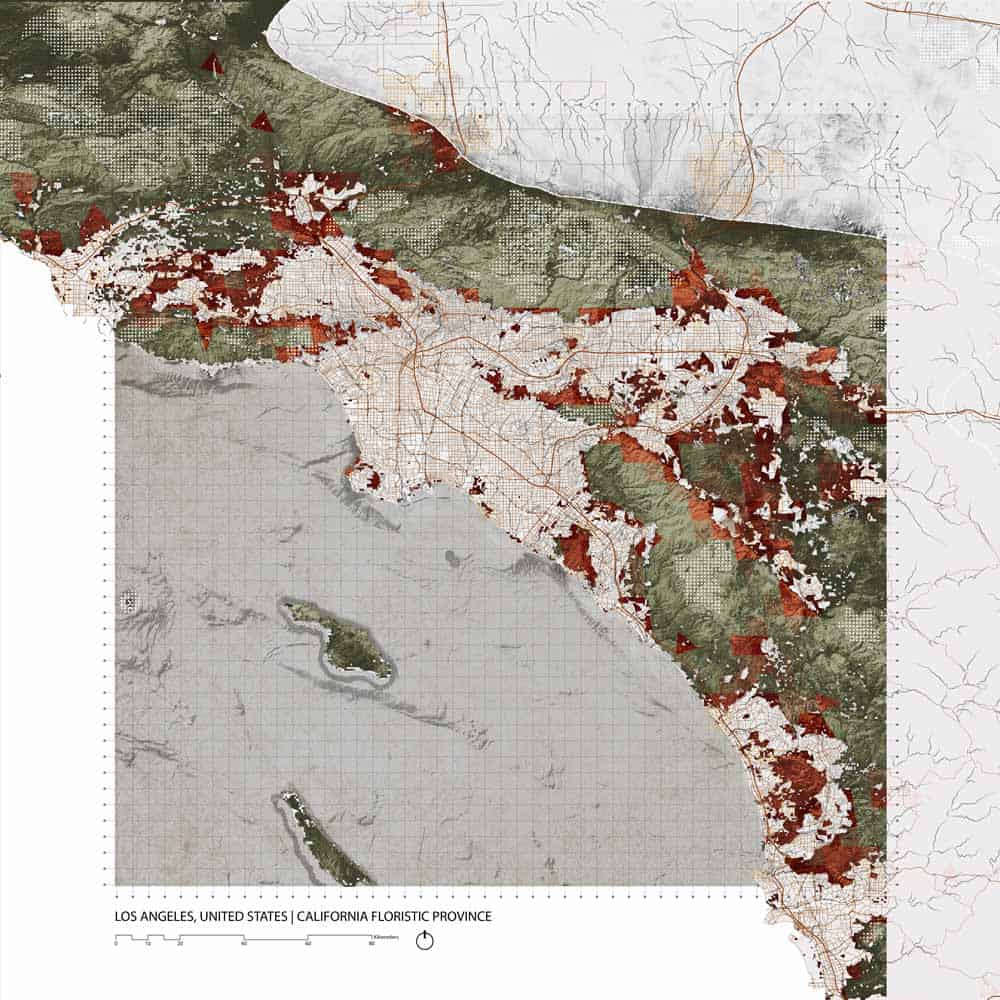

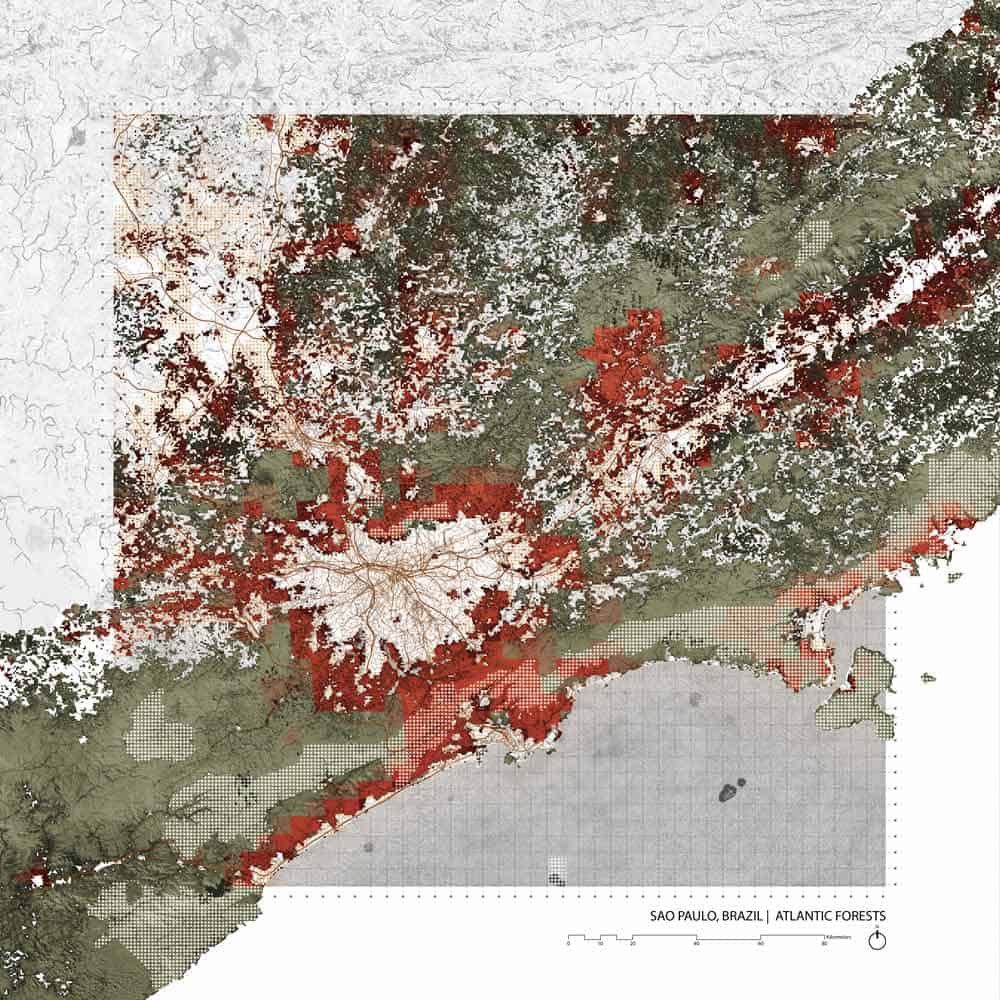

Integrating cities into the broader ecology of their regions is a land-use planning and urban design issue. Through detailed mapping and (desk top) analysis of a sample set of 32 major cities in the world’s hotspots, we have concluded that the majority have not adopted long term planning visions that include biodiversity values.

Los Angeles, one of 32 major cities in the world’s biodiversity hotspots. Red indicates zones of future conflict between urban growth and biodiversity. © Richard Weller

Sao Paolo, one of 32 major cities in the world’s biodiversity hotspots. Red indicates zones of future conflict between urban growth and biodiversity. © Richard Weller

A notable subset set of cities (examples include Sydney[4]Sydney Regional Metropolitan Area Plan: A Plan for Growing Sydney; Sydney Local Government Plan (Sustainable Sydney 2030), Perth[5]Perth and Peel Green Growth Plan (draft; not yet approved), accessed June 4, 2017., Cape Town[6]Cape Town Planning Portal, accessed June 10, 2017., Sao Paulo[7]Local Biodiversity Strategies and Actions Plan of Sao Paulo City, accessed July 12, 2017., and LA[8]Sustainability City pLAn, accessed August 6, 2017.), do however have transparent, readily available, variously integrated planning documents across levels of governance. A survey of the cities’ promotional materials, popular press, and institutional publications also indicates a low degree of cultural association with being ‘hotspot cities’. Typically, we also find that a city’s projected identity pertains to the characteristics of its urban core rather than its peripheral landscapes. A few cities–notably Cape Town, Perth, Sao Paulo, and to a lesser degree Los Angeles–have a robust narrative of their unique biodiversity, and their responsibility to preserve it.

The conflict between sprawl, resource extraction and biodiversity

By combining 2030 urban growth forecasts with endangered species data (IUCN Red List) shows where urban growth is in conflict with biodiversity[9]Our mapping is based on forecasts from the Seto Lab at Yale; See; Karen C. Seto, Burak Güneralp, & Lucy R. Hutyra, "Global Forecasts of Urban Expansion to 2030 and Direct Impacts on Biodiversity and Carbon Pools," Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States 109, no. 40 (2012): 16083-16088.. Having highlighted the problem, the question we must now ask is whether the growth trajectories of these sprawling hotspot cities can be redirected to avoid the further destruction of biodiversity, and if so how?

The conflict between sprawl and biodiversity cannot be approached reductively or simplistically as if sprawl (formal and informal) is only an outcome of economic and demographic growth, and conservation only a matter of fencing off areas in its path. [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”URBANET” suffix=””]The peri-urban territory of cities is a complex mosaic of different and often contradictory land uses in high states of flux.[/inlinetweet] Indeed, the alteration of peri-urban land is not caused solely by urbanisation but is also a consequence of extracting many of the resources required to support cities and their residents10text. The often invisible and myriad forces shaping these landscapes are not yet well understood by the urban design and planning professions, just as the novel ecology of these lands is not yet well understood by the scientific community.

A call for holistic research and realistic planning

The need is for case studies which approach the conflict between biodiversity and urban growth holistically. It is not enough to just cast anti-sprawl platitudes or make mere recommendations in planning reports that pay lip service to the Convention of Biological Diversity and the SDGs. What is needed are realistic spatial plans for these conflict zones, tuned to local cultures, which would concentrate urban growth in areas of least impact whilst simultaneously forging multi-scalar landscape connectivity for biodiversity. Upon the basis of sound socio-economic and ecological analysis, interdisciplinary teams can generate alternative urban growth scenarios which can show how conflict with biodiversity can be avoided. These scenarios can then be publicly evaluated for their costs and benefits.

It is our belief that a better understanding of peri-urban territory and the forces shaping it, is a prerequisite to the mitigation of further loss of biodiversity and that this is not only relevant to cities in the world’s biodiversity hotspots but to cities everywhere. As both the custodians and immediate beneficiaries of the unique biodiversity at their doorsteps, [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”URBANET” suffix=””]cities in hotspots have a global responsibility and leading role to play in integrating biodiversity with development.[/inlinetweet] To that end we propose that the hotspot cities come together to form a global knowledge-creation and knowledge-sharing alliance to support innovative urban design demonstration projects.

- Hotspot Cities - 17. January 2018